Monday, September 16, 2024

By Micah Gilmer – School of Law Public Affairs Graduate Assistant

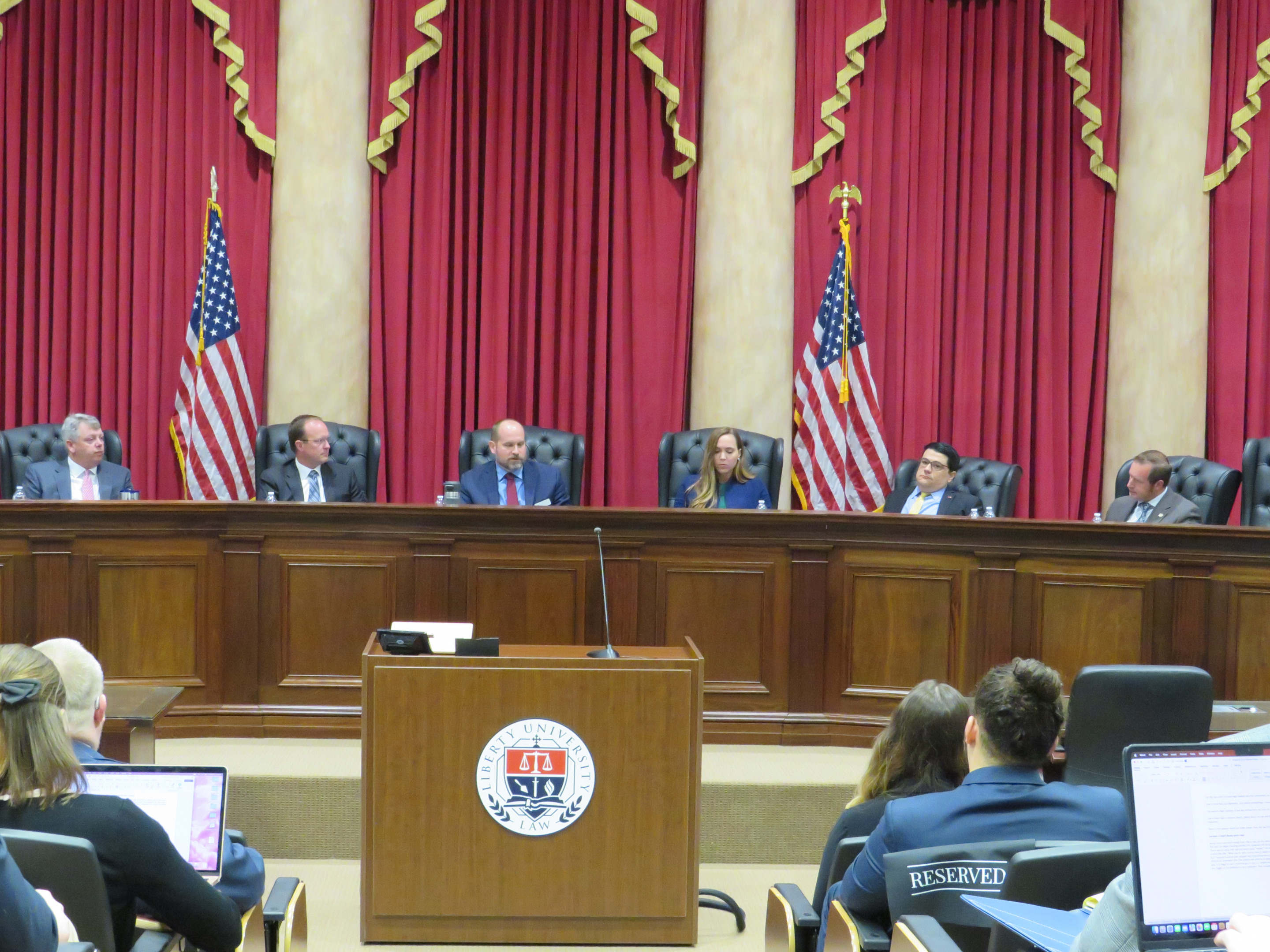

On Friday, Aug. 23, Liberty University School of Law held its annual Supreme Court Review, where Liberty Law professors participated in a panel to discuss some of the Supreme Court’s recent cases. The event was held in the law school’s Supreme Courtroom.

Ethan Payne, the editor-in-chief for the Liberty University Law Review (Liberty Law’s academic journal) opened the event with a word on how unique and important it was to be able to discuss these cases from a biblical perspective.

Dean Timothy Todd then spoke on the goals of holding the Supreme Court Review: “to spark and to encourage intellectual curiosity, to allow the faculty to exchange learned ideas and perhaps disagree (with) ideas, … to discuss commentary about recent cases, and to be a source of serious, rigorous, (and) academic thought in the Law School.”

Dean Todd also highlighted that the faculty presenters have partnered with the Law Review to provide articles that reflected each professor’s viewpoint on the case. The articles will be compiled in a special Supreme Court Review issue of the Law Review.

Dean Rodney Chrisman moderated the panel, and at the end of the discussion, the panel held a Q & A. Summaries of the cases and the professors’ insights are as follows:

Garland v. Cargill

Dean Chrisman discussed the first case, Garland v. Cargill. The question of whether a bump stock on a semiautomatic rifle turns a rifle into a machine gun has been heavily debated. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives took action to redefine a bump stock as an accessory that converts a rifle into a machine gun. This controversy led to Garland v. Cargill; the Supreme Court held that, because the definition of a machine gun relied on the function of the trigger and not the accessories accompanied with the gun, bump stocks do not convert a rifle into a machine gun. “Congress wrote words that do not cover rifles equipped with a bump stock, and since (those are) the words they wrote, we should hold them to that. If they want to cover something else, then they could,” Chrisman said. He noted also how this case has ties to the Second Amendment and emphasized how the Bible values the defense of life and property.

Murthy v. Missouri

Professor Natalie Rhoads presented Murthy v. Missouri, which came about after Missouri and Louisiana sued the federal government for encouraging social media platforms to censor particular views about COVID-19 and the election during 2020. Professor Rhoads noted that she was disappointed the Supreme Court evaded the question that many citizens still want answered: To what extent can the federal government encourage social media to censor views they don’t like? She added that because the majority of citizens use social media as their “virtual printing press,” the U.S. may not be dealing with a freedom of speech issue but a freedom of the press issue.

City of Grants Pass v. Johnson

Professor Erik Stanley provided insight on City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, which questioned if a city was allowed to enforce the prohibition of encampments of homeless people in public places. Stanley noted how, throughout the 20th century, several Supreme Court opinions regarding the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution — specifically the clause about cruel and unusual punishment — were unclear as to its extent. This led to Grants Pass. The Court decided that the Eighth Amendment allowed for the enforcement of these encampment prohibitions because the clause about cruel and unusual punishment focuses on the method of punishment and not whether an act can be criminalized in the first place. Professor Stanley agreed with the Court on this decision, as it brought about an important idea of limited jurisdiction: “God is the supreme judge. All jurisdiction is in Him and Him alone. He is the creator of all, and He alone has the jurisdiction, and so therefore, logically, man — (and) any jurisdiction we have — is thereby limited.”

Culley v. Marshall

Professor Wesley Vorberger presented the case Culley v. Marshall, which dealt with civil asset forfeiture. In the case, the two petitioners had loaned their cars to people who were criminally charged. The state seized the cars, and the petitioners, who were innocent owners of the property, filed class-action complaints, claiming they were not granted due process and wanted a preliminary hearing about whether the police were allowed to keep their property pending the forfeiture hearing. The Court’s opinion was that a preliminary hearing is unnecessary if the forfeiture hearing is timely. Professor Vorberger ended with two biblical insights. First, he sympathized with the innocent and socioeconomically disadvantaged owners of property involved in many civil asset forfeiture cases: “We don’t want to oppress the poor, and if that’s what this has … been doing, then we’ve got other problems.” Second, he read Ezra 10:6-8, which he argued had an account that shows a similar legal process to civil asset forfeiture. Connecting the passage in Ezra to the current case, he highlighted the main purpose of civil asset forfeiture: “If you’re going to live lawlessly, then we’re going to take your property.”

Acheson Hotels, LLC v. Laufer

Professor Tory Lucas discussed Acheson Hotels, LLC v. Laufer. The plaintiff, Deborah Laufer, had been acting as a “tester,” searching online for hotels that violated federal civil rights laws by neglecting to inform whether rooms were accommodating to people with disabilities. She sued numerous hotels for their oversight on this issue, even if she had no intention of staying at the hotel. This raised an issue of whether a tester has standing, and the case caused a split throughout the Court of Appeals. By the time it had reached the Supreme Court, however, Laufer had filed a suggestion of mootness, and the Supreme Court ruled in favor of said mootness. Professor Lucas focused on America’s continued systemic injustice to those with disabilities, comparing America’s treatment and segregation of Black people to its treatment and segregation of disabled people.

Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo

Professor Eric Bolinder spoke on Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which arose when a group of fisheries were forced to pay the salaries of government-contracted monitors under the Magnuson-Stevens Act. The fisheries argued that Congress had been unclear that this was allowed, which brought this case under a precedent set in the 1984 Supreme Court case, Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. This case maintained that when there is a lack of clarity in the statute, a court must defer the interpretation of the statute to the agency involved. Professor Bolinder remarked, “Judges are the ones that are supposed to be deciding what the law says, and in the Chevron formula, that power was taken from them, because judges were finding it ambiguous. … So who’s interpreting the law, then? The executive, because (the courts are) deferring to the executive.” In Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court overruled Chevron, giving the courts more authority to interpret unclear statutes. Professor Bolinder ended with a biblical perspective: “I would never say that the Bible mandates the outcome in Loper Bright, but you (see) stuff about, (not favoring) the rich, (not favoring) the poor, right? These are the sort of concepts that we should consider as we go through that (case).”

For more information regarding the Liberty University Law Review, please visit our website.