Graphic by Olivia Hess and Hannah Gilmer

Students are lazy. Students procrastinate. Students don’t want to think deeply. Students don’t want to learn….

Okay, enough of that.

If you are like me, you have heard these phrases dozens of times. Are they true? Sort of. Some students’ grades are tanking, and from personal observation, most of it has to do with a lack of personal discipline and ambition.

Raising the stakes for grades gets people working a bit quicker to turn in their assignments on time (or do them at all). This has been shown to be effective, according to the University of Pennsylvania, but many students, myself included, struggle when we are not given explicit instructions or breathing room to do our own thing within the guidelines of the class.

It is often the perspective that we start our classes with an A+, and any grade we receive lower than 100% means that we have lost points. So, we spend the rest of the semester trying to keep it as close to that A+ as possible. Normally, toward the end, we are sitting at our desks during finals week with our box of tissues and a calculator trying to figure out how to save ourselves. At this point, we will do anything to pass the class.

Is it fixable? Yes. It all has to do with mindset, but I will take us there in a moment.

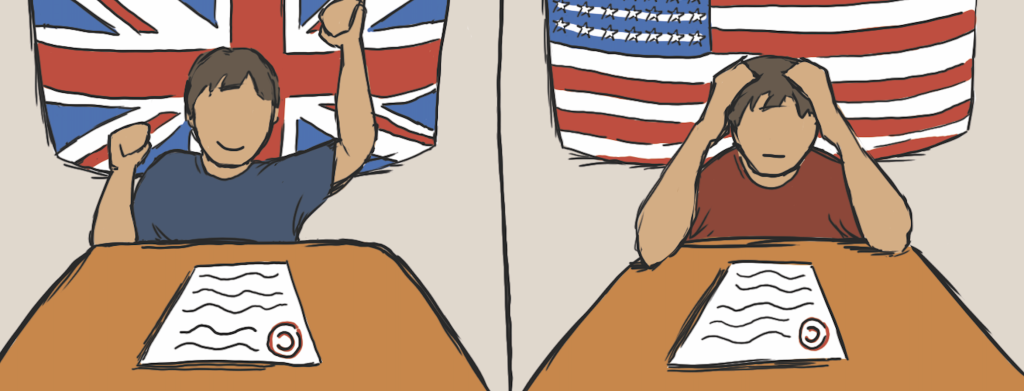

I am currently spending my spring semester in Northern Ireland, and here in the U.K., the grading system is entirely different. One of my professors, Ian Dickson, explained it this way: Everyone starts at zero, and getting a 65 is excellent. My heart dropped. A 65? Out of 100? Dickson also informed the class that he had not given anyone above an 85 in his many, many years of teaching.

Well, there went all my dreams and aspirations; these United Kingdom people were crazy.

But the more I experienced it, the more I thought that maybe their grading system isn’t so far-fetched after all.

Just look at Canvas’s grading system; it often calculates based only on graded assignments, making the grade constantly fluctuate rather than add up. This fluctuation — this teeter-tottering between letter grades — only causes stress for the student. However, from a more U.K.-grading perspective, starting at zero means you can’t lose points. You will only be “rewarded” for what you do well, instead of being “punished” for where you fall short. A D is “sufficient,” with a C being “satisfying.” Their percentages also allow some mercy, with it flowing in this order: 70-100% (A), 60-69% (B), 50-59% (C), 40-49% (D), 30-39% (E), 0-29% (F). So, it is possible to get an A, but as it has been explained to me, the point is not to get an A — the point is to learn.

In addition to this different grading scale, teachers in the U.K. promote individual work and critical thinking. They do not give listed, clear-cut directions because they want their students to be creative in how they execute their projects. It isn’t that the United States’ system has disregarded creativity and critical thinking, but because rubrics spoon-feed project details, it seems less available. Especially in United States’ public high schools, kids struggle to want to learn because the teachers do much of the work for them.

Starting at zero means you must fight to do well. You can’t decide what assignments not to do because, frankly, you need to do everything to pass the class. Working hard in school will promote working hard in other areas of life. Making assignments more fluid allows students to express themselves in ways that are better for their strengths and passions. No one likes studying something they don’t care about. Going up from zero also helps that grade feel like a big deal, instead of going through the motions of, “How could I have made that mistake?”

Even though the United States will not change its grading system, our perspectives can change. You can still apply yourself 110 percent to everything you do. You have nothing to lose, but you have everything to gain.

Johnson is an opinion writer for the Liberty Champion