Liberty University researcher embarks on project documenting freed slaves in Virginia

September 7, 2023 : By Christian Shields - Office of Communications & Public Engagement

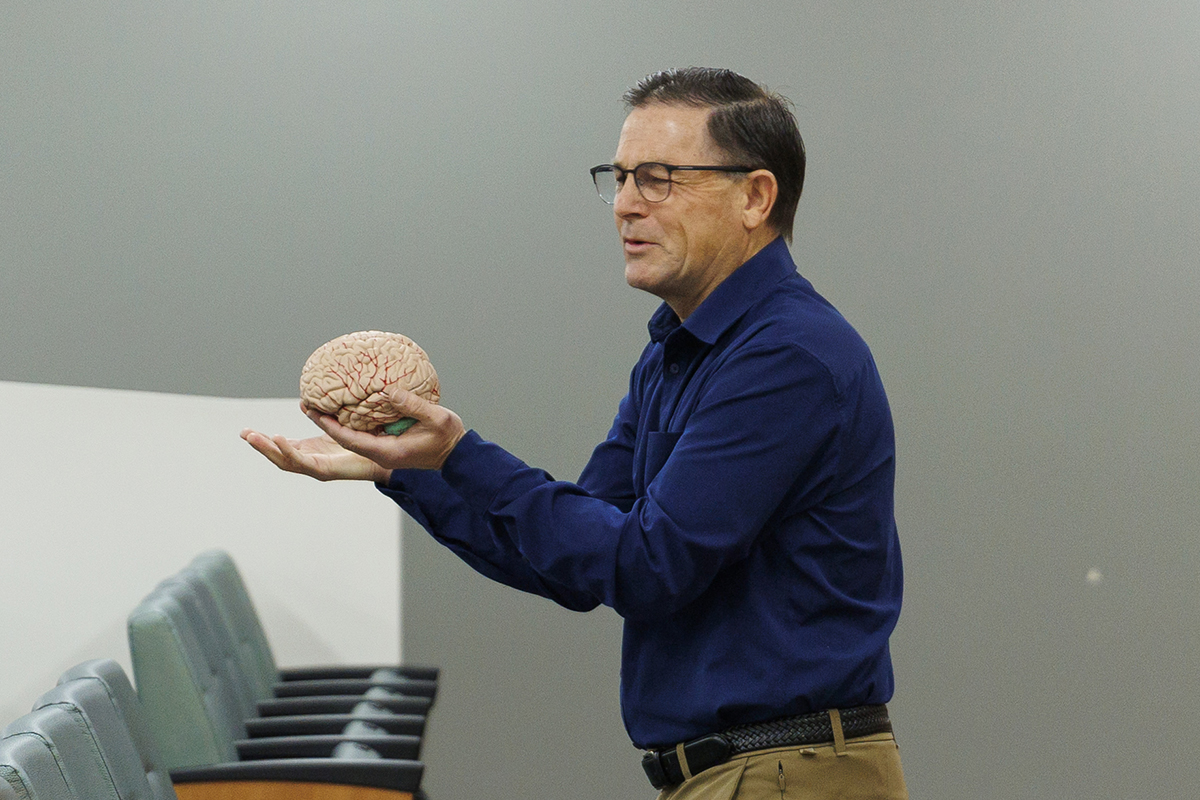

Liberty University Helms School of Government research fellow Andy Langeland (’22) is uncovering some of the often-overlooked and unaccounted aspects of manumission in Virginia’s history. Manumission was the formal process in which 18th and 19th century Virginia slaveholders, without any government order, voluntarily granted legal freedom.

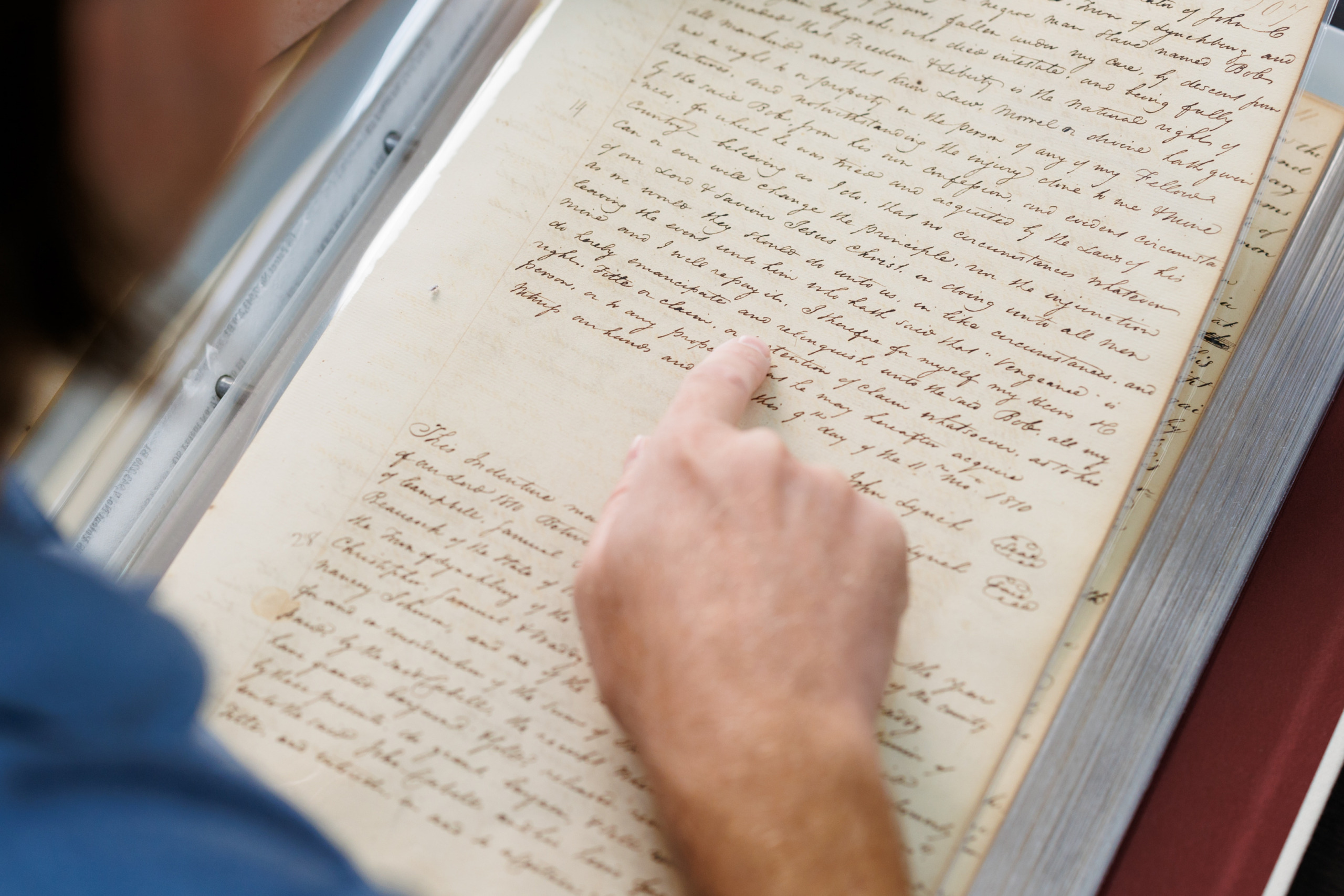

While there are similar research projects taking place around the country, Langeland is focusing on manumission cases in Virginia, combing through court documents and other government records. (In pre-Civil War America, manumission often happened through deed, when a slaveholder signed ownership over to the slave, or through a living will, when freedom was granted after the death of the slaveholder). Langeland said Virginia has the most cases of manumission in the country, with at least 5,000 cases recorded and at least 20,000 slaves freed in this manner.

Langeland said the purpose of the project is to educate the public on generally unknown historical facts and aspects of slavery in Virginia, dispel falsehoods and popular myths about freed slaves, and provide sufficient context to the historic facts. He is taking it case by case, filling in any biographical details he can find about the individuals and how they obtained their freedom so he can properly convey their stories.

“These manumission documents point to inspirational stories (of freed slaves) that have been largely overlooked and need to be rediscovered and shared to a broader audience,” he said.

While manumission documents exist, there is currently no digital catalog or master list for all the cases at the state level in Virginia. In addition, most of the current documentation is not digital or easily searchable.

Langeland first began the project after being approached by the Minnie and Bernard Lane Foundation while earning his master’s degree in public policy from Liberty. The local family foundation primarily works with community development and historical projects, such as the Avoca Museum in Altavista, Va. Langeland continued the work after graduation and recently became a research fellow at Liberty. So far, he has documented instances of manumission in the City of Lynchburg and five area counties (Campbell, Bedford, Pittsylvania, Charlotte, and Amherst) and has begun work in Albemarle County and Halifax County. He hopes to expand his research to all corners of Virginia while he pursues a doctorate in public policy. As the project grows, he plans to recruit Liberty students to help him reach this goal.

Last year, Langeland published a research booklet, “Manumission and the Advance of Christian Liberty in America,” with the Providence Foundation in which he documented case studies on leading Virginia families, including John Lynch, the founder of Lynchburg.

Through this research, Langeland said that until the late 1700s, the American colonies (later states) did not allow slaveholders to voluntarily free their slaves without the written consent of the governor or the state legislature (then called the House of Burgesses). In some instances, owners had inherited slave titles and were unable to legally and voluntarily free them even if they desired to do so. After obtaining American independence from the British Empire, several key states passed legislation to simplify the manumission process. After Virginia changed the law in 1782, many landowners from various socioeconomic classes were able to free slaves, including John Lynch, founder of Lynchburg, and his brother Charles Lynch.

Slaves freed through manumission would sometimes remain in their hometowns and could be seen actively working and participating in the community at large as freed men and women, Langeland said. He noted that research by Ted Delaney, the director of the Lynchburg Museum, has uncovered examples of freed slaves holding jobs such as hairdressers and dentists — two occupations that required a great deal of skill to perform and greater trust and support from the community. He said properly understanding the historic and unique context of manumission could go a long way toward educating people on a relatively unknown part of American history.

“It could be very positive for modern society to understand the nuance of the interactions during that time in American history. It can also shine a light on an aspect of race relations at a time when so many are fomenting animosity and division,” he said.

Langeland also noted that some freed slaves became landowners or entrepreneurs themselves, and several acquired enough resources to buy the freedoms of their spouses, children, and other loved ones.

Another aspect of Langeland’s research is showing how Christian values regularly played a key role in manumission, an action often perceived in direct contrast to societal norms. He also noted that some manumission documents included references to the Declaration of Independence and its rare notion that all men are created equal as well as Gospel messages and references to the Golden Rule.

“Historic court documents show us specific examples of the triumph of biblical principles over the world’s system, triumph of liberty over slavery, perseverance of free blacks in the face of many legal, political, and social challenges, and the strength of interpersonal relationships that superseded social convention.”