History students study artifacts from archaeological site at 18th century property during weeklong intensive

May 15, 2025 : By Ryan Klinker - Office of Communications & Public Engagement

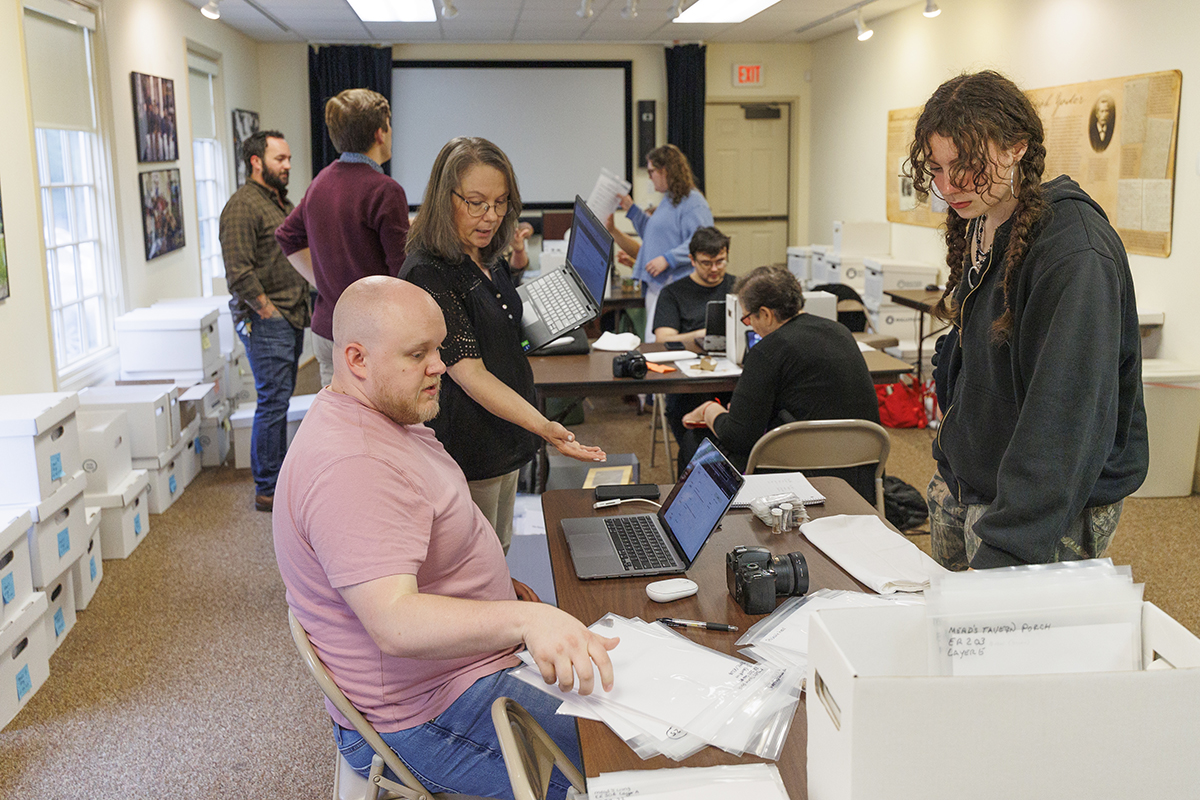

Eight students from Liberty University’s Department of History gathered over the this week to engage in an important step of the archaeological process after field work: identifying and organizing discovered artifacts with the purpose of historical interpretation.

Since being purchased by the university in 2015, Mead’s Tavern, the oldest standing structure in Central Virginia (built in 1763), has served as a living archaeological laboratory for Liberty students. The property holds significance for the historic town of New London, where travelers from the north and east would stop for food and lodging on their way to the frontier. In 2022, Mead’s Tavern was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Over the years, students have partnered with archaeologists and architectural historians from Hurt & Proffitt to complete a general survey of the property, excavations of the basement and porch, and make plans to turn a portion of the structure into a museum about Mead’s Tavern and the historic town.

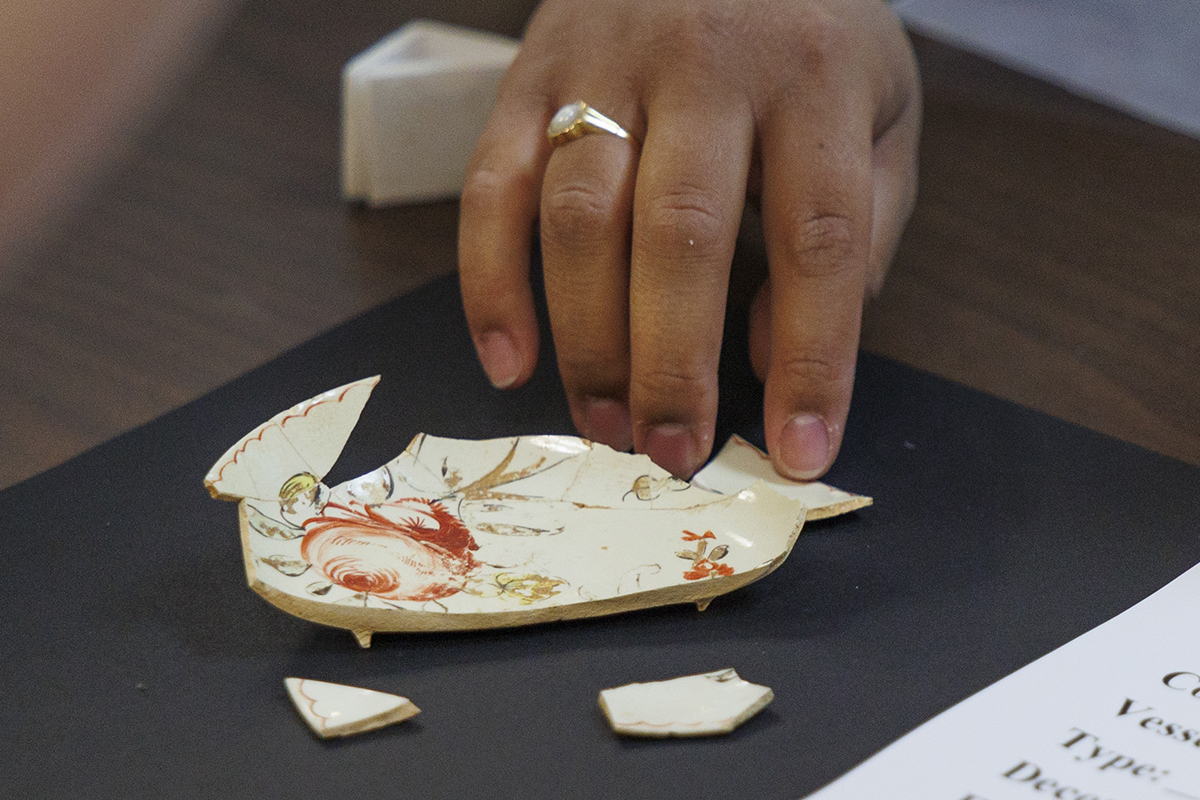

With over 100,000 artifacts from Mead’s Tavern cataloged in boxes, the students in the one-week intensive public history course are helping to research and document the items, which include ceramic sherds, buttons, coins, and clay pipe fragments, so they can be displayed in the future. The goal is to accurately describe and interpret the pieces and their place in history.

“Since we don’t have any active field work at the site right now, this is a way to get students involved with the other side of archaeology, because the largest percentage of what archaeologists do is actually after they retrieve the artifacts, bringing them back to be cataloged and processed,” said Director of Public History Initiatives Donna Davis Donald. “Part of the point of this class, in addition to learning lab methods, is to have students look through artifacts to select ones that are best for exhibit. We’ll be documenting those, researching them, and putting the data and photos together in digital form to eventually be made available to the public.

The group was divided into three teams working with different categories of artifacts: ceramics, tavern life (to include entertainment and refreshment), and firearms-related artifacts plus buttons and coins.

The intensive is being held on the property of Historic Sandusky, an estate that was once used as temporary headquarters for members of the Union Army during the Battle of Lynchburg in 1864 and a home visited by noteworthy American figures like Thomas Jefferson, Rutherford B. Hayes, and William McKinley. Today, it is owned by the University of Lynchburg and is home to the archaeology labs of Hurt & Proffitt.

Jessica Barry, director of archeological laboratories at Hurt & Proffitt, and other archaeologists are offering their expertise to the students in the intensive. The course was funded by the John and Blanche Steinhoff Memorial Fund, created through a bequest of the late Liberty history professor Dr. Mark Steinhoff with the purpose of providing students with experiential learning opportunities.

As a current student earning a master’s in history through Liberty University Online Programs, Collean Lufkin traveled from her home in Missouri for the intensive.

“I really like artifacts, and you learn more about how the people lived by being hands-on,” she said. “I love to step into someone else’s shoes and imagine what life was like in their time periods, and that’s why I’m taking this class. (Mead’s Tavern) touches on many different eras. I would recommend any online student to take an intensive course where you can do hands-on experience, because you’re going to learn in a new and different way.”

Jewel Kodavatikanti (’25) finished her bachelor’s in history through the course and is grateful for the opportunity to learn archaeological skills before leaving Liberty.

“Finding old (items) has always been a passion of mine,” Kodavatikanti said, recalling that as a child she would dig in the ground and find old pieces of metal or glass bottles and tell her mother that she had found “treasure.”

“Getting to work with actual pieces of history — items that are going to potentially be put into a display for Mead’s Tavern and teach people about Mead’s Tavern — is so exciting. Learning the techniques from the archaeologists here is a practical way to practice history and research that I’d never done before, and it has been amazing.”