Monday, October 2, 2017

By Gai Ferdon

The European continental Reformation (1400s-1500s) is known for producing an array of theological scholars whose writings attempted to either reform Roman Catholic institutions or replace them.1 Protestant Reformers, armed with vernacular translations of the Scriptures and a new approach to biblical interpretation, strategically attacked significant doctrinal assumptions critical to the Church’s authority as well as the ecclesiastical and civil institutions developed from them.

The Roman Catholic Church, for all intents and purposes, dominated the flow of information relative to the Scriptures. Most European laity were unschooled in Latin, without direct access to the Bible, and therefore, dependent upon the Priesthood to interpret its divine doctrines, which included its political and governmental truths. It was not until the Scriptures were made available in the language of the common man that individuals were able to infer a political theology with its corresponding civil/institutional emphasis. Protestant readings of the Scriptures resulted in new relational paradigms between individuals, communities and ecclesiastical and civil authorities.

The institutional consequences of the translation of the Scriptures into English, German, and French, resulted in a new constitutional relationship between rulers and ruled characterized by limited ecclesiastical and civil authority. Early modern political thinkers of Great Britain would seek to incorporate Protestant reformed political principles and methods of constitutional design to solve the constitutional crises brought on by the English civil wars (1642-1647), sometimes referred to as the Puritan revolutions. The British Interregnum (1649-1660) can be characterized as an attempt to new-model the ancient constitution through commonwealth structures, and patterned, in part, after the Old Testament Hebrew polity.

Protestant Bible Translation: A Vehicle for Reformed Theology in Service of Commonwealths

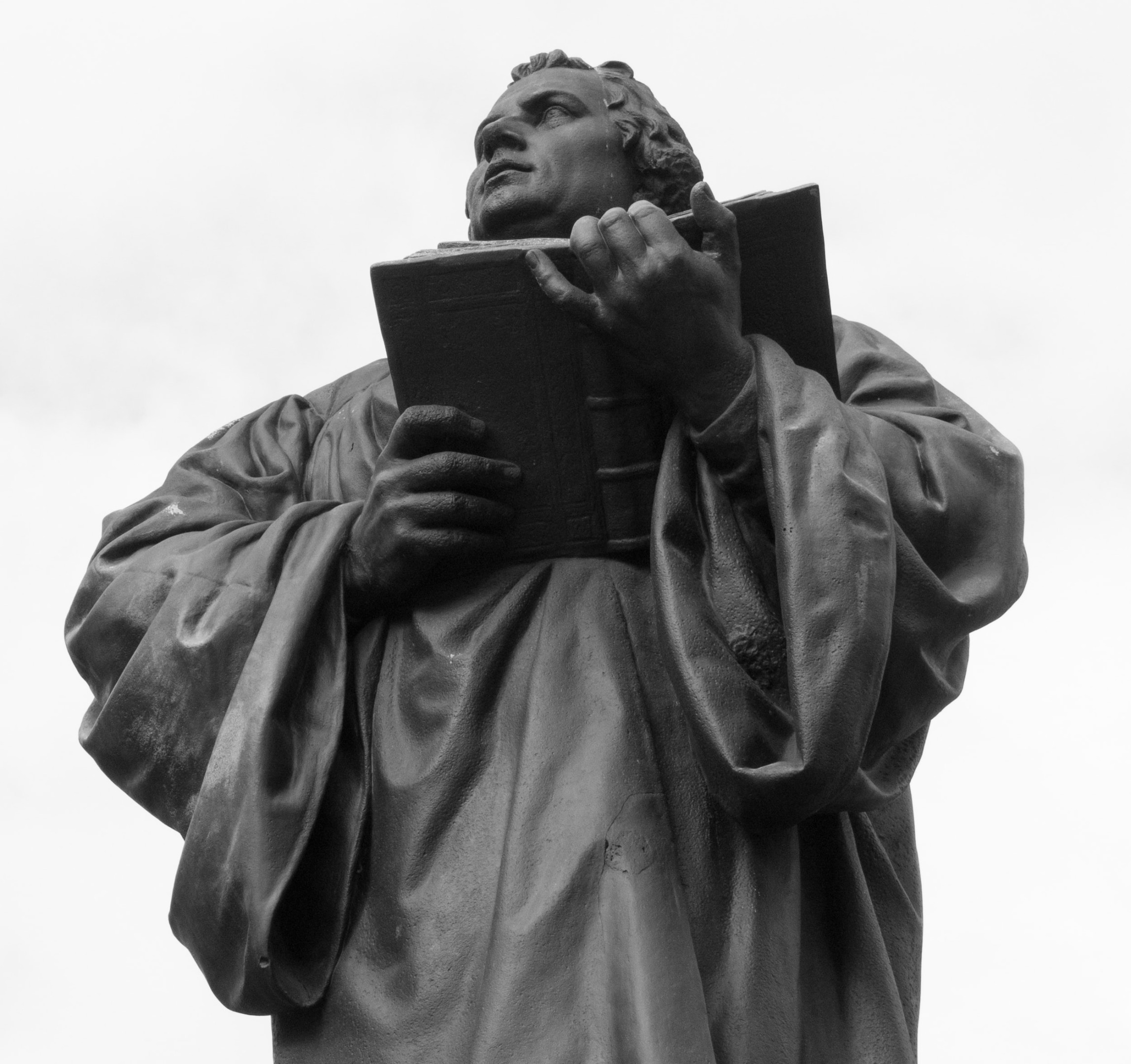

The German reformer Dr. Martin Luther (1483- 1546) is credited with formally launching the continental Reformation with his Disputation of Dr. Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgencies. Commonly referred to as the ‘Ninety- Five Theses,’ Luther publicly nailed his points of dispute with the Church to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. His subsequent writings would continue to attack the ecclesiastical absolutism of the Roman Catholic Church with its monopoly upon salvation and the Scriptures.

The leading French reformer was none other than John Calvin (1509-1564), who confronted the assumption that the Roman Catholic Church was the center and reference for life. Calvin forcefully declared that God alone bore absolute sovereignty over all of life, not the Roman Catholic Church, and therefore, every institution must be organized in submission to Him. Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) was an attempt, in part, at such institutional reorganization of the church and state through the application of the Scriptures. The Republican city-state of Geneva, Switzerland was Calvin’s institutional experiment to model a commonwealth upon Scripture, which subsequently impacted the ecclesiastical and civil structures of the New England Colonies, especially that of Massachusetts Bay.

There were a number of reformers who made significant contributions to the Protestant movement. Much could be said of the labors of men like the Bohemian Jan Hus (1369-1415), the Scotsman John Knox (1505[1515] – 1572), the Frenchman Theodore Beza (1519-1605), as well as the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531). The Reformation not only produced a wave of Protestant leadership, but Bible translations were being rapidly disseminated through Johannes Gutenberg’s press with its advent of movable type in 1436. Consequently, the Catholic hierarchy’s interpretive supremacy over the Scriptures was forever altered.

It was an Oxford professor who produced the first English translation of the Scriptures based upon Jerome’s 382 A.D. Latin Vulgate — the version used by the Roman Catholic Church. John Wycliffe (1320-1384), known as the ‘Morning Star of the Reformation,’ published his Wycliffe Bible in 1384. The German, Johann Gutenberg (1400- 1468) produced the Gutenberg Bible in 1455 and like Wycliffe’s, was translated from Jerome’s Vulgate. The Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) published his Greek and Latin Parallel New Testament in 1516 from Greek New Testament manuscripts then available, and therefore, apart from the Vulgate. Erasmus’s translation placed greater stress upon the importance of original languages in establishing textual authenticity and interpretation. Another Englishman, William Tyndale (1494-1536), translated the New Testament from Greek into English in 1526. Tyndale’s translation was followed by Miles Coverdale’s (1488- 1569) 1535 English Bible and then another, the very large Great Bible of 1540. Luther published his German New Testament in 1522 and translated the entire Scriptures by 1534.

One of the most controversial translations was the Geneva Bible (Breeches Bible) of 1560, with its first printing in England in 1571. A product of numerous reformed hands, including those who fled persecution in Britain under Queen ‘Bloody’ Mary Tudor (1553- 58), the Geneva Bible was the most widely read Bible in the English-speaking world. It underwent approximately 200 printings from 1560-1644, and was referred to as the Bible of the Puritans of Great

Britain and America. It is highlighted by its vast and influential sections of marginalia which incorporated reformed Calvinist interpretation, some of which directly attacked interpretive positions supportive of absolute civil and ecclesiastical authority.

A case of interpretive point is found in 1 Samuel 8:11 which rehearses Israel’s demand for a King like those of the surrounding Gentile nations. is chapter in particular has undergone quite imaginative interpretations over the centuries, and either in support of the absolute authority of Kings, or their very limited authority. As Samuel reminds Israel of the “manner of the King” in regards to property and servants, the Geneva translators supply their audience with an interpretation which emphasized divine limitations upon the authority of kings. Kings who rule outside their authorized bounds are ruling contrary to His will: “Not that kings have this authority by their office, but that such as reign in God’s wrath should usurp this over their brethren contrary to the Law (Deut. 17:20).” This interpretation proved quite unsupportive of monarchs generally, even Britain’s, and monarchical authority specifically.

Geneva Bible’s profound impact upon early American colonization is depicted in ‘The Embarkation of the Pilgrims in 1620,’ (1844) displayed along-side other prominent paintings of American history in the Rotunda of the U.S Capitol. Painter Robert Walter Weir depicts William Brewster sitting conspicuously with an open Geneva Bible — ‘The Pilgrims’ Bible’ — on his lap, with other outstanding Plymouth Colony leaders looking on.

A “New” Hermeneutic: Ad Fontes — Back to the Sources

Individuals who had access to the Bible advanced alternative interpretive methodologies which conflicted with the Roman Catholic Church’s standard approach. A Protestant hermeneutic was developing which laid greater stress upon the grammar and original languages of the Bible as well as its historical and literary contexts. Even Rabbinic and Jewish studies were incorporated into biblical interpretation. ‘Sola Scriptura’ produced, in part, a hermeneutic which employed Renaissance philological techniques with its emphasis upon history, grammar, syntax, original language analysis, and literary forms. The Geneva Bible incorporated this new hermeneutic.

Reformation Europe produced new political readings of biblical passages which resulted in radical constitutional ideas. ese newly developing political theologies were multifaceted in nature, challenging old perspectives on civil and ecclesiastical government as well as the authority of magistrates. ese emerging continental ideas were quickly making their way into England in the 1570’s as part of the Puritan movement, which included, among other sectarians, Republicans, known also as Commonwealthsmen, who contended against the Royalist political assertion that monarchy was God’s highest constitutional pattern by which men were to be governed.

A more detailed explication of the great hermeneutical debates emanating from the Reformation would reveal a new political theology advancing principles of liberty of conscience and religious liberty, civil liberty and limited civil government, separation of civil and ecclesiastical jurisdictions, equality under the law, government of laws, inalienable rights, popular consent and delegation of authority and power. Covenants became God’s relational paradigms through which to organize all of life, including political and ecclesiastical institutions, eventually transformed into republics and commonwealths.

It was none other than the great American statesman John Adams (1735-1826) who articulated America’s liberty-roots as grounded in the Reformation. In his 1765 Boston Gazette editorials, “A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law,” Adams addressed this “wicked confederacy between the two systems of tyranny,” or between ecclesiastical and political magistracy, which restrained the advance of “liberty, . . . knowledge and virtue.” It was not until “God in his benign providence raised up the champions who began and conducted the Reformation,” that tyranny was transformed into liberty.

From the time of the Reformation to the rst settlement of America, knowledge gradually spread in Europe, but especially in England; and in proportion as that increased and spread among the people, ecclesiastical and civil tyranny, which I use as synonymous expressions for the canon and feudal laws, seem to have lost their strength and weight. . . .

It was this great struggle that peopled America. It was not religion alone, as is commonly supposed; but it was a love of universal liberty, and a hatred, a dread, a horror, of the infernal confederacy before described, that projected, conducted, and accomplished the settlement of America.2

As we celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, let us remember, restate, and reaffirm the great liberty-roots whose seeds were planted by reformers courageously challenging the tyranny of their day with biblically inspired truths — truths which eventually birthed and inspired the foundations of the United States of America — and redeploy them to confront the tyranny of our own time.

1. This article is adapted from the ‘Introduction,’ to a previously published monograph by Gai Ferdon, The Political Use of the Biblein Early Modern Britain: Royalists, Republicans, Fifth Monarchists and Levellers (Cambridge, UK: Jubilee Centre, 2013), and with permission from the Jubilee Centre. Interested readers can access the entire monograph for free at https://www.jubilee-centre.org/?s=Ferdon.

2. John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, Notes and Illustrations, by his Grandson Charles Francis Adams, vol. 3, The Works of John Adams; Autobiography, Diary, Notes of a Debate in the Senate, Essays (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1856), 451, OLL, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2101.