A professor and two students stood around a small object tangled in a thin, barely visible net in the cool November night air.

“How about the scissors first. Come in here and snip that thread first,” Dr. Gene Sattler, professor of biology at Liberty, said. “Now take the crochet hook and catch those few threads and go the other way, up here, and we are going to take it right off the wing.”

After a few minutes of meticulous pulling, cutting, twisting and turning, a saw-whet owl emerged from the net, wide-eyed and beak snapping in defense. Another student came in to hold the owl, gripping the legs right at the body. The owl flapped its wings a few times before settling into its new perch.

“We have one over here,” a student, only visible by her headlamp, yelled from one of the other five nets which stretch a total of 180 feet through the woods.

Another bird had blundered into the nets, drawn to the area by an audio lure making a male saw-whet’s mating call. Sattler set off through the woods with crochet hook and scissors in hand to free the 11th owl of the night, the most they had of any night this fall. As he untangled the last owl, the other students, with an owl in each hand, began the 15-minute trek down the trail, around the lake at Camp Hydaway and to the white trailer where they would catalog and band the birds.

Most fall nights since 2002, Sattler can be found here, working with students and providing them hands-on experiences with these tiny owls. Sattler has a permit through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries to band saw-whet owls.

“It’s mostly about benefiting the students,” Sattler said. “Here we are able to do research where the students are there side by side with you. It gives them an advantage.”

Many of his students, freshmen through seniors and particularly zoo and wildlife majors, have aspirations to work in zoos. This field experience and one-on-one work with a professor help students stand out after graduation and supplement their in-class education.

Beyond the opportunities these evenings banding owls provide students, the research also contributes to the study of saw-whet migration, particularly in the South.

Northern Saw-whet Owls, one of the smallest species of owls in North America, breed primarily in New England, Canada and the West. They feed predominantly on woodland mice, so in the winters when their breeding territory is covered in snow, competition for food gets fierce and many migrate south. However, little is known about their migration and population in the South, so research is important for understanding their migration dynamics and for conservation efforts.

“We don’t have a good picture of the density and distribution,” Sattler said. “There are very few people banding in the South because there are such small numbers, so there are big holes in our understanding of just how many are down here.”

Liberty is one of only three banding areas of this species in Virginia. Saw-whet owls are not very vocal outside of breeding season, so prior to the start of this project, there were only two confirmed records in the Lynchburg area, one is 1959 and another in 1980. While Sattler and the students only had the nets open for two weeks this fall, they caught and banded 24 owls. Their record for the most in a season was 102 owls in 2012.

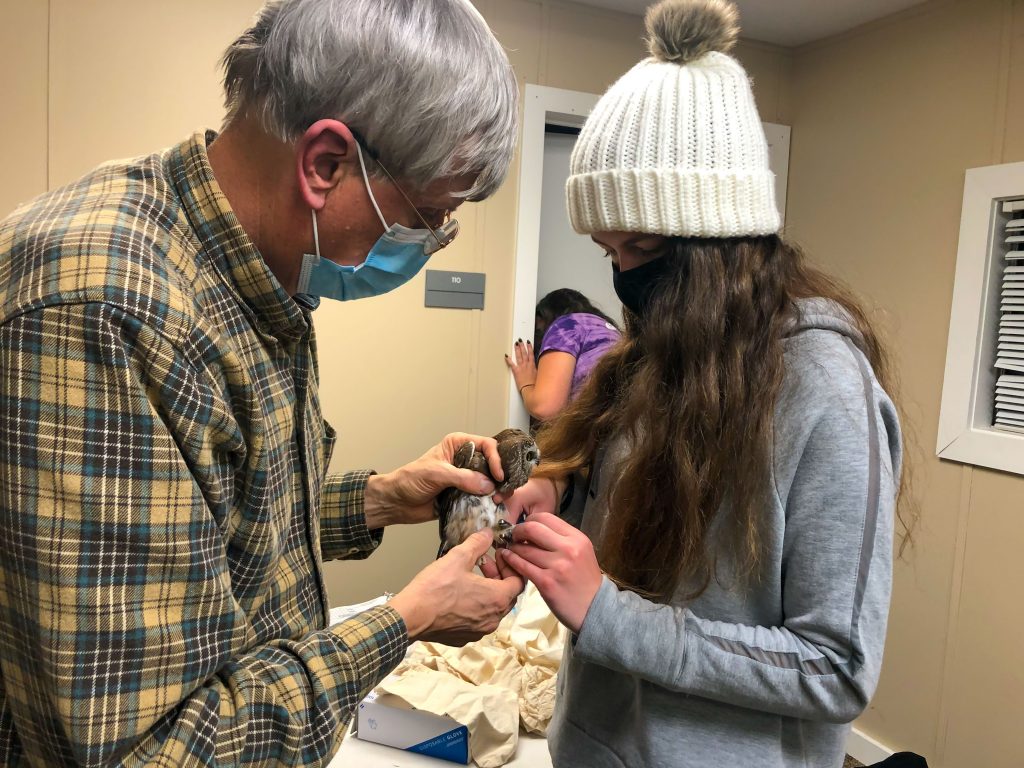

The students record the weight, wing length, fat content and molt patterns of every owl they catch as well as the night’s moon illumination, cloud coverage and wind.

With the wing length and weight, they are able to determine the bird’s sex. Females, which are usually larger, make up 80% of the birds they catch.

The molt patterns, determined using an ultraviolet light that causes blood in new feathers to fluoresce, help determine the age of the birds. If all of the feathers fluoresce red, it is a hatch year bird born that spring while a mixture of old and new feathers indicate that it is at least one year old.

The data goes into an online database maintained by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Bird Banding Lab that helps ornithologists better understand the bird’s populations in the South.

After collecting this data, the students band the bird by placing a small metal ring with a unique identifying number on its leg. These bands allow birders to know when their owls are caught somewhere else. Sattler has caught owls previously banded by scientists all along the east coast, and owls he has banded have been caught as far away as Alabama and Wisconsin. They have not caught one of their own birds from the previous year because saw-whet owls tend to be more nomadic and do not follow the same migration pattern from year to year.

After allowing them to readjust to the dark, Sattler and the students release the saw-whet owls back to the wild. The owls fly up into a nearby tree, reaccustom themselves to the area and soar off to continue their migration or perhaps stay in the area as nearly silent neighbors throughout the winter.

Jacqueline Hale is the Feature Editor. Follow her on Twitter at @HaleJacquelineR.