The minds of youth are precious and pure. Parents and every sort of group hopes to keep them that way as long as possible, leading to censorship in schools — specifically regarding banned books.

Certain books in schools face bans due to religious groups or overly-concerned parents and other parties.

The list of challenged books includes “Their Eyes Were Watching God” and “Native Son.”

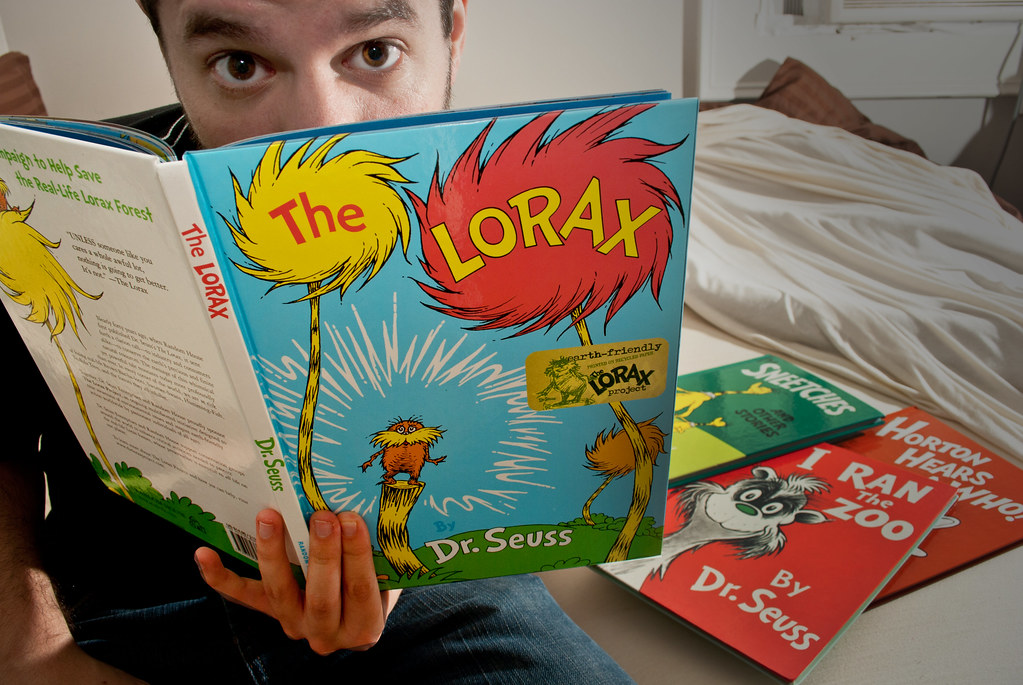

The list of banned books includes “The Lorax,” “Hop on Pop” and “Captain Underpants.”

What could possibly be the reasoning behind banning “The Lorax” due to the political nature of the story versus banning “Native Son,” which details a rape and murder scene with the perpetrator then running away?

“Tess of the D’Urbervilles,” which is allowed and sometimes required reading in many schools, includes rape, murder, infant death, a criminal running from the law and then the death by hanging of the main character. Yet “Hop on Pop,” a children’s book, is no longer allowed.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Everyday Health condemns the general idea of censorship at all. They claim that parents cannot protect their children forever. While that is true, there are certain ideas that don’t need a place in a child’s mind.

There must be a middle ground somewhere in this entire argument. Parents can not protect their children from everything, yet some themes have no place in schools.

I understand that schools need to prepare youth for the real world that isn’t all daisies and roses. However, put good in and get good out. Schools wonder why anxiety and depression run high in high schools. Granted, bad books aren’t the only cause, but they certainly aren’t helping.

Mary Collins from the Christian Science Monitor wrote that her kids and their classmates take notice of the monotony of depressing themes in required reading. She even mentions how her daughter shied away from reading because she was required to read so many books with downtrodden and violent plots that she lost interest in fiction.

Another problem lies in the lack of continuity of book challenges across state lines. A book banned in Alaska might remain in the curriculum in Texas. For banned books to actually create an impact, there must be some sort of standard that schools can use to compare books against.

If a book is deemed ineligible for schools in one state, why is it allowed in another? The system itself defeats its own purpose. Keeping one state’s children from reading inappropriate content does nothing if the state next to it requires its students to endure the reading.

This issue is bigger and needs more discussion than just Banned Books Week in September when attention is drawn to the lists of banned books. A line must be drawn in the sand of where protection meets censorship. Schools can’t protect children forever, but a shield of defendable reasons for banning books is necessary and entirely possible.

The splintering of a solid base is confusing and unnecessary. While the nation needs to include more uplifting selections to reading lists, none of that will matter if the standards are not equal.