Why “Exodus: Gods and Kings” fails to inspire

Reviewed by Dr. Randall Price

We all know that Ridley Scott can inspire. He did it with “Gladiator.” In that film, he took a soldier who became a slave and pitted him against the king of Rome. And in the midst of this conflict of two wills, the character of the hero was revealed to be praiseworthy and inspiring.

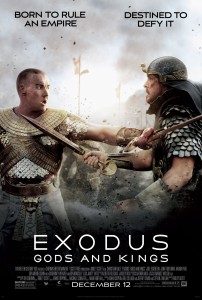

In theaters now — The biblical movie is showing in theaters across the country.” width=”202″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-27340″ /> In theaters now — The biblical movie is showing in theaters across the country.

In theaters now — The biblical movie is showing in theaters across the country.” width=”202″ height=”300″ class=”size-medium wp-image-27340″ /> In theaters now — The biblical movie is showing in theaters across the country.In his new film “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” he had the same opportunity. Here, a soldier who became a slave was pitted against the king of Egypt. However, in the contest of wills that ensues, the character of the hero (if we may call him that) continually diminishes itself so that we are less inspired at the end than at the beginning. And to leave any audience unmoved as the credits begin to roll should be considered the worse verdict any film or director could receive.

I have done some reflection about why, despite the breathtaking CGI effects, I was so unmoved by the climax of the film.

In the first place, the story of the exodus is well known, not only from the Bible, but also in the annual rehearsal of its drama in the 3,500 year-old tradition of the Passover — something barely seen and left unexplained in Ridley Scott’s film. Next to the story of Jesus, there is no account more revered by people of biblical faith. An audience that included such people, potentially numbering in the tens of millions, would be an audience already charged with a high level of expectation.

However, no one, nowadays, expects Hollywood to not exercise artistic license and to revise its adaptation of the biblical text (and there are plenty in this film). Directors, it seems, just cannot be shackled with having to make their script conform to scripture; the revision plays to a modern audience so much better. After all, who wants the Bible to be boring?

But even allowing for this inevitability, a faith-based audience anticipates a film experience that touches their faith, especially when the source for the film is filled with ten miracles plus a splitting of the sea. To be sure, Scott employed the best effects Hollywood has to offer to visualize all of this, but to this reviewer, each effect fell flat because there was no real cause for the effects.

In the biblical drama, the cause is the God of the Hebrews demonstrating his incomparability in light of the Egyptian pantheon and the pharaoh as their representative. There is a hint of the latter, but hardly a whisper of the former. It is bad enough that the God of the Hebrews, invisible to all others in the film, appears to Moses as a petulant child having difficulty making up his mind about things. The contest of wills in the Bible is between God and pharaoh; in Scott’s reinterpretation, it is between pharaoh — the real lead — and Moses. As a result, the producer, who may have thought he had created an intensely human interaction, created a cinematic Maginot Line, a strategy that people hope will prove effective but instead fails miserably.

This concept worked with “Gladiator,” so why not with “Exodus?” In “Gladiator,” we were met with equally pagan characters; no faith was required, even though there was a display of pagan devotion to the Roman gods. Yet, nothing in that drama required a god to save the day or to define the events that unfolded. The focus remained centered on the human actors and their contrasting characters that brought either disgust or admiration. Therefore, we were moved.

In “Exodus,” the plot required divine intervention on a grand scale. This equally required a contrast in the characters as they responded to the overwhelming reality of God in their midst. But in this case, Moses struggles with God as much as pharaoh, or perhaps even more. Miracles just happen without being tied to an announcement of God’s person or power. Moses is told to be a bystander and just watch and do nothing. In the Bible, he is God’s direct agent, who manifests a personal relationship with the Almighty.

Here, in my opinion, may be the inner motivation behind Scott’s depicting the Almighty as a little child (one with scratches to boot) and depicting an unstable Moses as habitually unsure of his intentions — If one does embrace the concept a personal deity, one cannot depict him as such. Failing to give personal attention to the Main Character (God), and to credit him with Israel’s salvation (the only suggestion of this is the upraised hands of a few), the depiction of miracles seems hollow, and the plot feels flat.

In the Bible, Moses cannot be explained apart from his relationship with God. It is that relationship that motivates him, empowers him and enables him to lead the multitude through the wilderness. Moses knows God and will not allow any trial or temptation (even from God) to diminish his absolute confidence in God’s promise-keeping character (see Exodus 32:1-14). The absence of this kind of God in Scott’s version made even the miracles somewhat boring and left the audience feeling more sympathy for Rameses than Moses. Here, for me — and I am sure for countless others — is the Moses I never knew (and, frankly, do not really care to know).

If the world grants success to this film, it will be more of a sad statement of where our post-biblical culture is today than on the quality of one more prime season release blockbuster. Sadder still is the fact that this post-biblical and biblically illiterate culture may never realize just how far such a biblically inspired film is from the Bible itself. This, then, is the real shame, for while Scott’s film fails to inspire, the Bible never does.

Dr. Randall Price is distinguished research professor and executive director of the Center for Judaic Studies at Liberty University. He has been involved with numerous Bible-based film and television documentaries and has directed five documentaries in the Holy Land based on books he has authored.