By Emily Brown

World War II veteran recalls horrors of war and God’s protection over him

Survivor — George Rogers endured many harships throughout the war but managed to triumph over his circumstances. Photo credit: Taylor Streelman

At 95 years old, George Rogers has defied the odds. Doctors said he was not supposed to live past 45 or 50 years old. But Rogers is still here, his smile and laughter contagious to all those around him. Despite the horrors he faced as a prisoner of war for three and a half years at the hands of the Japanese military during World War II, Rogers is the picture of joy.

Seventy-four years ago, when George Rogers stepped through the doors of the recruiting office at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri, Aug. 20, 1941, all he wanted was to avoid the bad stigma attached with being drafted rather than enlisting. What Rogers got in return was far from what he expected.

As a young 21 year old, Rogers followed the advice of the major in charge, who convinced Rogers that the Philippines was the best place to be as a soldier. The Philippine Islands were “a poor man’s paradise,” as pay was $21 a month, according to a biography written by Rogers’ wife.

Only two months after arriving in the Philippines, on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and U.S. troops, including Rogers, were put on high alert. After doing their damage in America, the Japanese arrived in the Philippine islands the next day. U.S. troops, along with Filipino soldiers, were forced to retreat to Bataan, hoping that help would come soon.

But it never did.

With no relief, American and Filipino soldiers were forced to survive on meager rations. But soon, the amount of food became the least of the soldier’s worries.

Nearly four months to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, on April 9, 1942, Bataan fell, and the U.S. troops there were forced to surrender. Japanese forces put the weak, malnourished U.S. and Philippine soldiers through an unthinkable task — a task known today as the Bataan Death March.

The soldiers — approximately 10,000 Americans and 62,000 Filipinos — were forced to march nearly 75 miles (120 kilometers) in less than one week. During the walk, soldiers were regularly beaten for falling out of ranks or disobeying an officer. And in addition to the fear of being beaten or bayoneted, the marching soldiers were deprived of the very elements they needed in order to survive — food and water.

“One hundred and twenty kilometers may not seem too long, but when you’re hungry and (have) no food, no water, that’s a long way, particularly when there’s a bayonet that could end your life if you fell back or fell out of ranks,” Rogers said.

Although no exact numbers are known, the estimated number of deaths ranges from 10,000-18,000 men.

After the 75-mile trek, Rogers and his comrades were put to work doing hard labor at Camp O’Donnell in the Philippines for four long months.

“In my mind, it was not hopeless, because I was content that if God wanted me to live, I would,” Rogers said. “He would see to it that I would. All that he expected of me was to wake up every morning, do the best I could, do everything in my power to live that day, and that’s the way I worked. You have to have the will to live in a situation like that. I can’t express enough words … to have you feel what it was like to be in that concentration camp.”

At Camp O’ Donnell, Rogers was assigned the morbid duty of digging graves for dead and dying soldiers. According to Rogers’ biography, he dug graves three feet deep, six feet wide and 10 feet long — enough space for 10 soldiers to be buried.

According to Rogers, soldiers who died at the makeshift hospital were taken outside and placed under the building. As if digging the graves was not enough, Rogers was also made to drag those dead soldiers out from under the building in order to bury them.

With a severe lack of medical care, thousands of soldiers were left to die.

During one of his trips under the hospital, Rogers pulled himself through the dirt in the three feet beneath the building and grabbed a soldier he thought was dead. But the man was not dead. The boy Rogers grabbed turned his head toward Rogers and called out, “Not yet, buddy. Not yet.”

More than 150 graves later, Rogers had helped to bury 1,600 Americans.

After completing four months of grueling work with little food and water, Rogers was moved to Cabanatuan, where he spent the remainder of his 25 months in the

Philippines, according to his biography.

At Cabanatuan, Rogers faced strict orders from the Japanese and received quite a few bruises at the hands of his commanders despite not doing anything wrong. Every time he was knocked down by the fist of a Japanese commander, he popped right back up, avoiding a bayonet in the back.

On top of the beatings Rogers received, he and his fellow soldiers suffered through extreme pain in their feet and legs due primarily to dry or wet Beriberi, a disease affecting the nerves and muscles.

Worse than the pain in the soldiers’ feet and legs, however, was the disease that ran rampant through the camp. Amoebic dysentery, a disease highly contagious that was known as a death sentence to all who contracted it, devastated the camp. Soldiers who were diagnosed with amoebic dysentery were immediately quarantined.

Rogers was one of those soldiers.

For six months, Rogers laid alongside the sick and dying, thinking he might soon be added to the casualty list.

But Rogers was misdiagnosed.

“This is the Lord working, because I was exposed to all these men with dysentery, and I did not contract it,” Rogers said. “… Praise the Lord, first, for that six months of rest, and second, for protecting me from that highly contagious disease.”

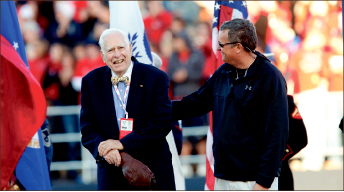

Family — George Rogers (left) stands with his son Jeff during a ceremony at Liberty

University, which honored him with a statue placed at Williams Stadium. Photo credit: Les Schofer

And after avoiding death once again, Rogers repeated the feat when he survived malaria, which he contracted later in his stay at Cabanatuan.

Although Rogers and his fellow soldiers had already faced and overcome a number of obstacles in the Philippines, their journey continued as they moved to Japan in July of 1944.

According to Rogers, in the process of transporting soldiers, he barely missed the first ship out, which was attacked and sunk by American forces. For Rogers, God showed up again by protecting him and keeping him from getting on the first ship.

“I was glad I didn’t make the first ship,” Rogers said. “That’s just another indication that God was in control of my life.”

After making his way onto the second ship, which housed 1,500 soldiers in a space made for 500, Rogers panicked as he faced the crowded conditions.

“I almost lost it, and then … I got a peace that came over me, and I just felt everything is going to be alright, just relax,” Rogers said. “As far as I’m concerned, God was at work again.”

After an 18-day trip with barely any food or clean drinking water, extreme heat, rampant illness — both physical and mental — and no chance for soldiers to wash themselves outside of being hosed down every few days with ocean water, all 1,500 men somehow finally made it to Japan. The soldiers stayed at Fukuoka and were then transported to Yawata Steel Mill, where they worked 11 hours a day.

According to Rogers, U.S. troops were forced to do hard labor, some of which included rebuilding ceilings in furnaces. While working there, the prisoners of war could only face the blistering heat of the furnace for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, and they had to hop from foot to foot to keep from severely burning their bare feet.

A year after arriving at the Japanese camp, on Aug. 8, 1945, American bombers dropped incendiary bombs on Yawata Steel Mill. Most soldiers escaped serious injury.

While the prisoners expected to return to work following the bombing, they did not. For the malnourished, tired soldiers, the work reprieve signaled something big.

A few days later, Japanese commanders vacated the camp. After more than three years of arduous work, horrible conditions and hardly any food or water, the U.S. prisoners of war knew the war had finally come to an end.

According to Rogers, as he was being transported out of the region, the officer in charge told the soldiers that the second atomic bomb, which was eventually dropped at Nagasaki Aug. 9, 1945, was destined for Yawata Steel Mill Aug. 8. Overcast skies prevented the attack.

Rogers said he has made no attempt to verify the information and simply praises God for the weather.

Although Rogers had not accepted Jesus Christ as his Lord during his four and a half years in the Army — three and a half years of which he spent as a prisoner of war — he now understands God’s goodness throughout all the trials he faced.

“I was not born again when I was in service, but I did believe in God, and I felt like he was going to protect me,” Rogers said. “In so many ways, he did.”

After being transported back to the U.S., Rogers — a gaunt, 6-foot-3, 85-pound version of his former self — was given medical treatment and counseling about his experiences as a prisoner of war.

“There was a team of three psychiatrists that talked with us individually, and they (asked), ‘Well, how do you feel about the Japanese?’” Rogers said. “And I said, ‘Well, I was just at the wrong place at the wrong time.’ And they said, ‘Well, isn’t there any animosity? They didn’t treat you right.’ And I said, ‘Well, they did not treat us right. They didn’t feed us well. They didn’t clothe us well. We didn’t have enough shoes. But there again, I’m a soldier boy. I was at the wrong place at the wrong time.’”

But the psychiatrists would not accept his answer.

“They kept pounding away (and asked), ‘Well, aren’t you angry with the Japanese?’” Rogers said. “I said, ‘No, not really. They were just trying to do their job as I was trying to do mine.’ So they finally let me know (that) they thought I was really lost. I mean, they thought I was gone for sure because I had no animosity toward the Japanese whatsoever. And I really didn’t. I really didn’t.”

Rogers said he has ultimately learned invaluable lessons from his experiences.

“What I learned in concentration camp was beneficial the rest of my life,” Rogers said. “It was just living one day at a time, doing the very best you can, living the best life you can. And, of course, now I know that the Lord is with me whenever I decide to do something.”

Following his time in the military, Rogers continued to defy the odds.

Although doctors informed the prisoners of war that they would likely lose their hair, teeth and eyesight, Rogers still has all of those things today. Although doctors said those prisoners of war would likely never be able to succeed in school, Rogers received a four-year degree from St. Louis University in only three years and graduated with a 3.2 GPA. Although doctors said those prisoners of war would likely never have children, Rogers has five children with his wife, Barbara, the girl of his dreams. The two have 14 grandchildren. Although doctors said those prisoners of war would likely not live past 45 or 50, Rogers is still alive today, displaying a contagious joy, at 95 years old.

Rogers was awarded a Purple Heart and Prisoner of War Medal for his sacrifices during World War II.

Now, in addition to being a hero of the U.S. Army, Liberty University has welcomed Rogers as a highly honored member of its community. Following more than 20 years of service to the university, where he last worked as vice president of finance and administration, Rogers was honored for his service with the U.S. Army. A statue now stands at the gate of Williams Stadium, the home of the Liberty Flames football team, as a tribute to Rogers for his sacrifices.

Brown is the editor-in-chief.

*All quotes taken from a Liberty

University-produced documentary.