Al Worthington is 92 and pitched to his last batter in the major leagues a full half century ago. But he still receives several letters each week from passionate baseball fans. They ask for an autograph. They tell him they enjoyed watching him pitch for their beloved Twins, Reds, or White Sox. More than a few tell him he was one of their favorite players because of his deep commitment to his faith.

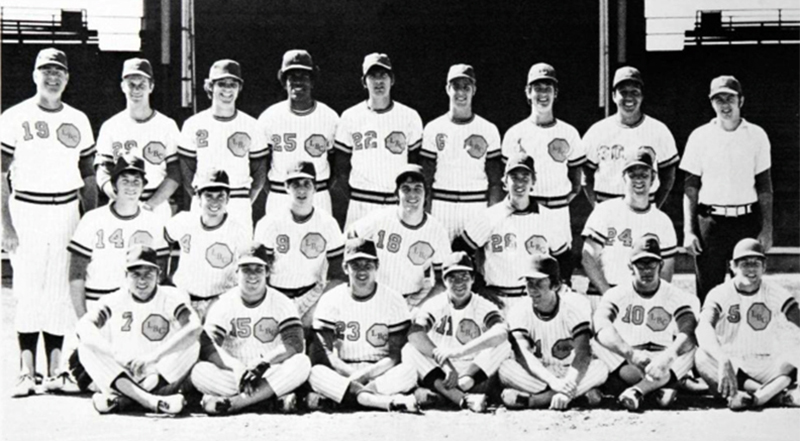

Al Worthington with Jerry Falwell Sr. and players in 1979

Age long ago took the baseball from his hand. His accomplishments in baseball and as a highly successful coach and athletic director at Liberty University more and more belong to the past. But his commitment to his faith has not lagged or dimmed. Worthington’s morning ritual is to laboriously handwrite individual responses to the fans and stuff the envelopes with Christian literature.

Worthington built the baseball program at Liberty with an integrity rarely seen in big-time college sports. He was so devoted to his faith as a stalwart major leaguer that his unwavering devotion nearly overshadowed his World Series stints, rookie records, and other sports accomplishments. A story on him in a major magazine in 1963 was headlined “A Bible in the Bullpen.” And in a move that stunned the baseball world and has never been done before or since by such a prominent baseball player, he once abruptly quit the game rather than cheat.

“I am biased, but I call him the original Tim Tebow,” says his daughter Michele Adkins, a 1981 Liberty graduate and an adjunct professor of psychology at LU.

A Sports Great

Worthington, born and raised in Birmingham, Ala., and now living near the city, still speaks with a tight-lipped, lovely Alabama drawl. “I can’t do everything I used to do, of course,” he says. With his need for a cane, he no longer cuts the grass. But he does the dishes. He attends church three times

a week.

Al Worthington at a Liberty Baseball Homecoming reunion in 2013

Family keeps him busy and happy. He and his wife, Shirley, married since 1950, have five children, 13 grandchildren, and 16 great-grandchildren.

Baseball also has a way of still occupying his time. He made it back to Liberty in October 2019 for the dedication of Worthington Field at Liberty Baseball Stadium. (This was not his first such recognition: the Flames played baseball at Worthington Stadium from 1979 until the program moved to its new facility in 2013.)

The honors were well-deserved.

As baseball coach for 13 seasons, starting in 1974, his squads won 20 or more games for 12 consecutive years. His overall record was a sparkling 343-191-1. LU finished fifth in the NAIA World Series three straight years from 1981 to 1983. His star players included Sid Bream, later a Pittsburgh Pirate and Atlanta Brave, and Lee Guetterman, an eventual Seattle Mariner.

Al Worthington (top left) with Liberty’s first baseball team in 1974

As athletic director for 16 years, he led the tremendous growth of athletics at LU. The Flames rose from NCAA Division II to Division I in 15 intercollegiate sports.

Worthington oversaw the expansion and fielded winning teams while keeping out the negative elements that sadly often creep into college sports. He kept a Bible on his desk in his office. “Christ is my manager,” he once told a reporter.

Today, Worthington fondly remembers what he tried to do at Liberty and how it worked out. “I was a professional athlete. I was taught to win. I taught my players that. But they had to do it the right way.

They didn’t cheat,” he says. “My players didn’t get into trouble or quit school. They had a different attitude about life (than other college athletes). They tried to work with me, not against me. They tried to do the right thing. That’s what Christians do.”

He’s troubled that the Houston Astros stole catchers’ signs in 2017 through a video camera in center field. “That’s just wrong. That has to be stopped,” he says.

Those are not the words of an armchair moralist. He once packed his bags rather than bag his faith.

A Fateful Day

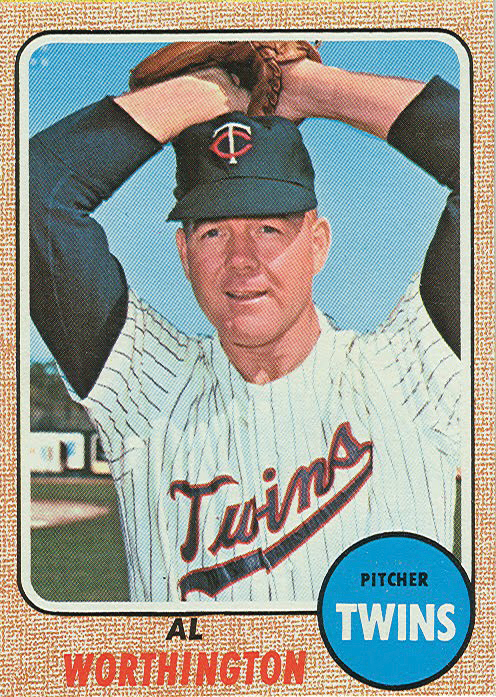

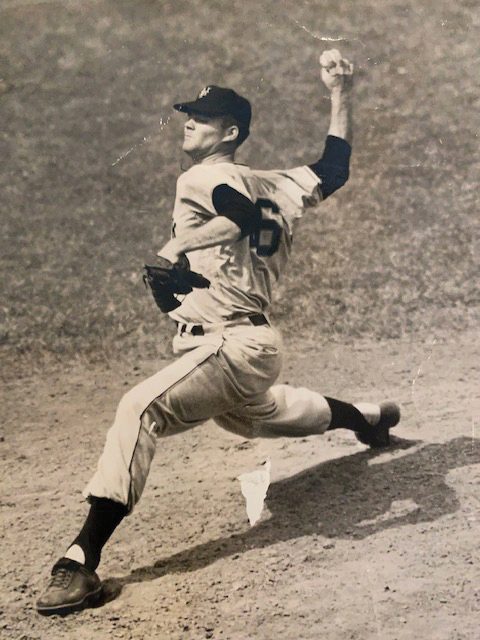

Worthington broke into the majors in 1953 in a big way with the New York Giants. He became the first National League rookie to throw shutouts in his first two starts. He became a solid, reliable pitcher.

He had been religious since a child, but his faith was routine, not a passion but a habit. That all changed in 1958 while he was with the San Francisco Giants. Sports had been the center of his life. He was an established major leaguer. He was physically fit, handsome, and healthy. His marriage was on firm ground. But he felt an aching emptiness.

He had been religious since a child, but his faith was routine, not a passion but a habit. That all changed in 1958 while he was with the San Francisco Giants. Sports had been the center of his life. He was an established major leaguer. He was physically fit, handsome, and healthy. His marriage was on firm ground. But he felt an aching emptiness.

“I was tired of leaving home and going on road trips, living in hotels,” he wrote in his autobiography, published in 2004. “The years of sports that I played did not give me the peace I wanted.”

A teammate, Bob Speake, invited him and Shirley to the famous Cow Palace to hear Billy Graham. On the second night, arriving late, they sat in the top balcony in the aisle. After Graham preached and as a large, energetic choir sang about Jesus, his heart began to pound. He could not resist: he found himself pulled to the main floor, to the growing crowd in front of the stage. His heart had broken. “I decided to give God my life and surrender my all to Him,” he wrote.

Worthington began speaking to church groups, sharing and spreading his faith. Honesty and integrity, at home and in the workplace, was paramount, he told congregants. So he was especially disturbed when he discovered that the Giants that season had planted a spy with binoculars in the outfield grandstands to relay what pitch was coming.

Worthington began speaking to church groups, sharing and spreading his faith. Honesty and integrity, at home and in the workplace, was paramount, he told congregants. So he was especially disturbed when he discovered that the Giants that season had planted a spy with binoculars in the outfield grandstands to relay what pitch was coming.

Worthington knew the desire to win often trumped right and wrong, but he boldly approached Manager Bill Rigney and told him the cheating was wrong. Rigney agreed to stop using the binoculars, Worthington says (though Rigney publicly maintained the team had not used a spy). After the season, not surprisingly, Worthington was traded.

After a stint in the minor leagues, Worthington ended up with the Chicago White Sox in September 1960. Saddled with a history of futility, the team was finally battling for a pennant, and Worthington quickly endeared himself to his new teammates and rabid Sox fans by winning a game and saving another.

To his dismay, he learned the White Sox also were cheating by posting an employee with binoculars in the scoreboard. He approached Manager Al Lopez in a hotel lobby in Kansas City and told him, “What we’re doing isn’t right.” Lopez basically told him to mind his own business.

Worthington then talked with Sox executive Hank Greenberg, who told him everybody cheats a little to win. “I’m a Christian. I can’t go along with something that is dishonest,” Worthington replied. Shaken to his core, Worthington packed his bags and went home to Birmingham.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do for a living,” he told the Saturday Evening Post. Baseball was aghast at what he did. Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby said he ought to “pitch in the Humane League.” Others were less kind, saying he belonged to the “Ladies Church League.” The White Sox tried to sell his contract, but the “word was out that he was some sort of cuckoo,” said Greenberg.

Life After Baseball: More Baseball

A bust of Al Worthington sits in front of the Liberty Baseball Stadium.

A bedroom in the Worthington home is dedicated to sports memorabilia. There are photos, trophies, uniforms and so on — 16 years immersed in sports at Liberty and 14 years in the big leagues leave plenty of traces. Yes, after being initially disowned by professional baseball, professional baseball welcomed him back. The desire to win also apparently meant forgiveness, baseball-style. The next spring after he quit, unable to trade him, the Sox astonishingly told Worthington to report to their minor league team. For two years, he blew the ball by overmatched minor league hitters. Still, no major league team would take a chance on him.

Then, in desperate need of pitching, the Reds signed him in 1963. He pitched well, and at the team party after the season they playfully presented him with a pair of binoculars. His career continued to flourish. In 1965, he was voted the best pitcher on the Twins and appeared in two games in the World Series against the Dodgers. When he finally retired in 1969, he was the oldest player in the American League.

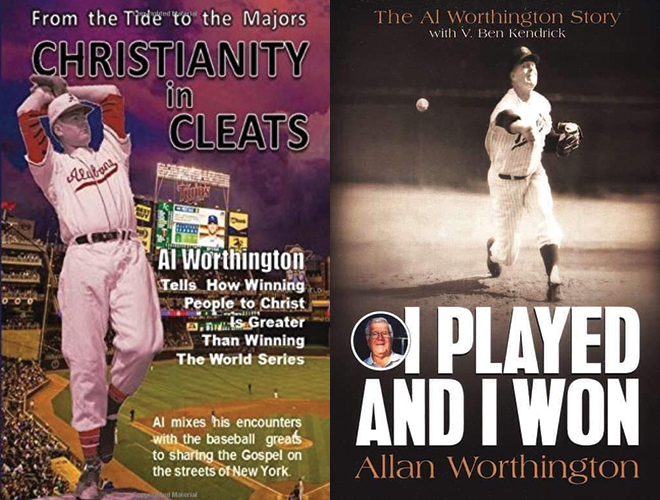

Al Worthington has authored two books about his baseball career and his faith.

It all worked out. “You have to trust God,” he says today.

He also trusted God he was doing the right thing in 1973 when he eagerly sought out the Rev. Jerry Falwell, founder of Liberty University (then Lynchburg Baptist College), to coach its first baseball team. He greatly admired Falwell and wanted to work for him. “I loved it. It was a challenge, but it was such a good place.”

He’s entrusted his children and their children with the university: besides Adkins, his two sons, Marshal and Daniel, are graduates, and a granddaughter is a freshman.

In major league baseball, by the time he retired, Worthington was fondly known as “Old Reliable.” For Worthington, the story has been the same since that fateful day in San Francisco in 1958: he’s relying on a higher power.