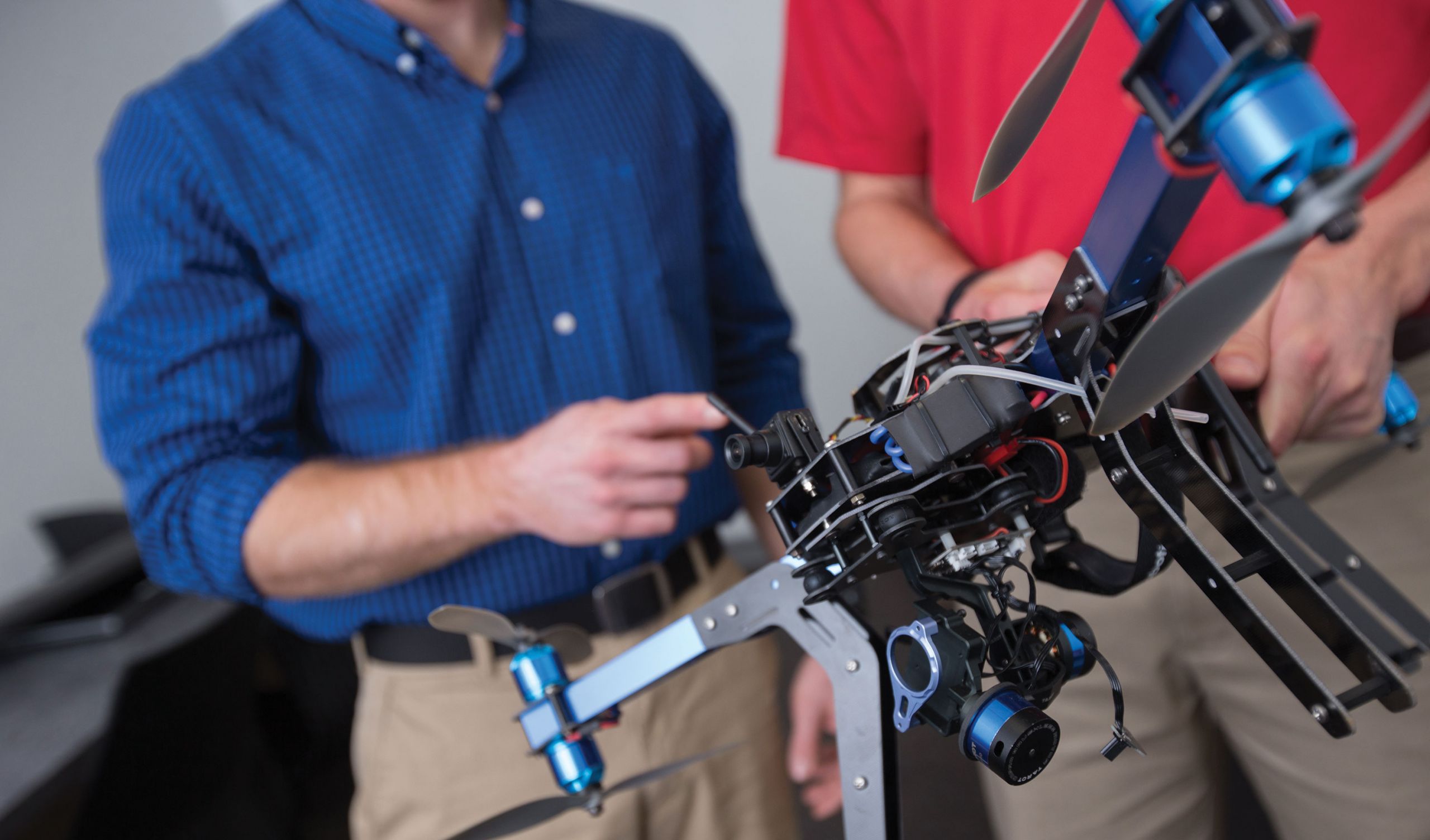

Jacob Miller (right), a senior in the School of Aeronautics’ UAS program, gets some hands-on experience with a 3D Robotics Y6 unmanned aerial vehicle under the supervision of professor Jonathan Washburn.

The future is looking up — literally — as Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), the technology used to remotely pilot unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, commonly called drones), begin to revolutionize day-to-day operations for a variety of industries. On the cutting edge of this rapidly growing field, Liberty University School of Aeronautics (SOA) offers a residential Bachelor of Science in Aeronautics that includes UAS operator certification.

While a world with UAS presents unique challenges — the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is preparing to release its regulations for how to incorporate UAVs into national airspace this summer — Liberty saw the potential to train professionals in this industry years ago. Administrators foresaw the many possible applications for these high-tech devices, not only in the intelligence community and the military, but also as a means to improve everyday life by minimizing risk and increasing efficiency in areas as diverse as crop-dusting, utility inspections, and disaster relief.

“First responders such as firefighters, police officers, rescue personnel, and search and rescue teams can use these systems to do their jobs faster and safer,” said Jonathan Washburn, the Liberty aeronautics professor who leads the UAS program.

And when time is critical, as when teams are searching for someone lost (and potentially injured) in a large area, having an eye in the sky can make a life-or-death difference.

UAVs can also be used to inspect oil, gas, and power lines, as well as utility towers, so that those who repair them can do their jobs more efficiently. An unmanned vehicle, for example, could fly long stretches of power line to locate damage. In agriculture, a UAV could be used to help farmers locate specific areas that have flooded or need fertilizer, pesticide, or water, minimizing the use of chemicals.

“UAS will not replace hands-on, physical repairs,” Washburn clarified. “Early on, they will augment those roles, helping workers with efficiency — a more targeted use of manned systems.”

When disaster strikes, employing UAVs not only helps with spotting potential threats — such as compromised infrastructure or blocked roads — but they can also be used to quickly deliver aid without putting a pilot in danger.

“The list grows steadily as aircraft are built or adapted to carry out new tasks,” Washburn said. “Yes, unmanned aircraft were and still are used to great effect in the war environment. However, the use in civilian airspace takes that platform and opens up a growing list of uses that will benefit all of us in some way in the years ahead.”

The upcoming release of FAA registration and use requirements will pertain to small UAVs (classified as any unmanned aircraft under 55 pounds) for corporate and civil use.

“Once those rules are published, it will define the industry a little better and allow for a bit more stability,” Washburn explained.

Law enforcement agencies, the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Department of the Interior are already utilizing UAS, and once the regulations are released, civil applications are expected to expand significantly.

Charting a course for excellence

In 2012, the university began training students in this up-and-coming field.

“I believed it was imperative that we only added and retained programs that would guarantee our graduates opportunities for employment,” said Dave Young, Liberty’s assistant provost for aeronautics education. “It became apparent to me that the world of Unmanned Aerial Systems was going to grow exponentially, and if we were going to be a viable university aviation program, then we should enter it full force.”

Liberty’s program has become a model for UAS training. A year after it started, it received the Innovator of the Year award from Virginia’s Region 2000 Technology Council. The program soon established relationships with companies on the forefront of UAS creation and deployment, giving students an advantage when job-hunting after graduation.

“Almost immediately our students and graduates found this to be a lucrative job market,” Young explained. “In fact, at the time, we even had some current students take a sabbatical from school to accept well-paying yearlong positions as UAV operators.”

Graduates from Liberty’s UAS program have secured jobs at industry leaders such as Textron and Navmar Applied Sciences Corporation.

At the end of 2013, the FAA authorized six public entities across the U.S. to research and test UAS. The Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP), led by Virginia Tech, is a joint venture between universities in New Jersey and Virginia‚ including Liberty University. Liberty staff have provided vital expertise and helped secure funding for the MAAP UAS testing and research site.

“We have an incredible opportunity to provide our students with real-world flying and testing of unmanned systems right here in Virginia,” Washburn said. “It is my goal to see LU students and graduates working with the FAA and other industry partners at the test site to solve some of the problems facing UAS integration into the National Airspace System.”

Washburn graduated from Liberty in 2007 with an interdisciplinary degree in aeronautics and video production. He joined the SOA last summer after working for four years in the UAS industry, both as an operator and in research and development.

Although Liberty is among several schools across the country offering UAS training, its program is distinctive in that it teaches both the technical aspects of UAS as well as UAV operation. Students build a solid foundation in aviation, earning their FAA private pilot’s license and instrument certifications while also being trained in the latest UAS technology.

“We are training operators who are professional and have a deep understanding of aeronautics, not just a surface knowledge of how these systems work,” Washburn said. “We want them to be able to adapt to any size vehicle.”

Landing the best resources

Industry partnerships also bolster Liberty’s UAS program. Not only are students able to work with the most cutting-edge systems, aircraft, and control software while in school, but they can also get full operator certification.

Liberty has a partnership with Textron Systems, a company that operates the Aerosonde UAV — a medium-sized aircraft (with a wingspan of a few meters) used by the U.S. Department of Defense and NASA, among other agencies.

“This level of certification is highly sought after in the industry, and we are seeing our current students and graduates find jobs based on the experience they have flying this platform,” Washburn said.

The Aerosonde is too large to be flown in the general use airspace near Liberty’s campus. The SOA overcomes this challenge by taking students to an off-campus location where they can actually fly the aircraft, an invaluable learning experience. On campus, students have access to a UAS simulator lab, and the university is acquiring both fixed-wing and multi-rotor UAVs that will be used to train students to fly the smaller aircraft allowed by the FAA in national airspace.

“These small UAVs will allow us to teach fundamentals of command and control as well as the skills required to fly safely,” Washburn said. “That builds into courses where more advanced systems are taught in the classroom, and eventually students will learn to fly the Aerosonde UAS through our partnership with Textron. Our small UAS and the Aerosonde UAS are leading systems that provide solid and proven platforms that can advance with the technologies of the future.”

Piloting the future

Liberty is in the process of receiving FAA approval to fly these smaller aircraft on its property.

In December, the university purchased the New London Airport, a public-use airport in Bedford County about 13 miles from main campus that will serve as a lab environment for aviation students. Young said it will be especially beneficial to the UAS program because students should be able to operate UAS more readily in the noncommercial airspace, pending upcoming FAA regulations (the SOA utilizes the Lynchburg Regional Airport, which is airspace restrictive to UAVs).

“We will be able to create a learning environment where students can practice the skills they learn in the classroom, making them even more sought after to fill critical aviation positions,” he said.

The 134-acre airport, featuring a 3,100-foot runway, is home to about 50 private aircraft. Operational since 1958, the airport maintains a traditional aviator culture where veteran pilots trade stories as younger ones learn to fly. Liberty plans to preserve that culture while also supporting Liberty’s Flight Training Affiliate (FTA) program. Students across the country can log flight hours at qualified FTA locations as they earn a Bachelor of Science in Aeronautics degree online through Liberty. (The FTA program currently includes over 40 affiliates across the nation.) The site will also be used to host regional, state, and national conferences and seminars. Other academic programs, such as business and engineering, may use it as well so that students can gain practical experience in a functioning aviation business.

Because the UAS industry is constantly changing, flexibility has been important to the success of Liberty’s program.

“We are working very hard to keep the courses and materials up-to-date as well as build a program that offers students the chance to learn how to operate both small and large UAS,” Washburn said. “In the future, there will be new courses offering deeper knowledge of the systems used to fly UAVs as well as the addition of small UAS that the university will own — and the School of Aeronautics will operate — to both train our students and to perform various photo and video functions for the university.”

The small UAVs could, for example, be used to take aerial photographs of a Flames Football game or campus construction.

Taking off from a firm foundation

As UAVs begin to stretch their wings in airspace, it is likely that some of the concerns people have will only amplify. Some worry about privacy. Others (more extremely) fear mindless robots patrolling the sky.

“As with anything in life, when something is not understood, it will typically lead to fear,” Washburn explained. “Right now the vast majority of unmanned aircraft, even the most advanced cutting-edge designs, still rely on a human to make most of the decisions. The aircraft does fly on its own, but the computers are only capable of automating flight — using the aircraft’s control surfaces to maintain stable flight. Any choice about where to fly, what to look at, or what actions to take — apart from level flight — are all sent from a human operator.”

For the automated systems to operate ethically, they rely on ethical operators.

Ethics have always been a foundational element of a Liberty education, and the UAS program is no exception. In fact, Washburn stresses how vital it is to the future of the industry.

“We work to build a strong foundation of ethical problem-solving and consideration,” he explained. “We are using the incredible biblical knowledge our students are getting in their worldview courses and helping them to apply it when answering ethical questions. Privacy is a very real concern and one that all of the people flying unmanned systems will face. It is important that our students are ready to face those challenges and to do so from a Christian perspective.”

Jim Molloy, dean of the SOA, believes that because of this foundation, Liberty graduates can emerge as leaders in the industry and positively affect how it is shaped.

“We are not just providing UAV training and pilot training,” Molloy said. “Our curriculum is strong in leadership skills, ethics, team skills, mentoring, written and oral communication, critical thinking and problem solving, safety, and many other key soft skills that industry, government, and missions organizations are craving. We teach our students how to be leaders, even when they are not leaders in the formal sense of position and title. Aviation is not a discipline in which you can take shortcuts or perform at less than your best. Professional aviators must be disciplined, competent, and proficient every day.”