Lynchburg honors Ota Benga with historic marker where he died

- Lynchburg unveils historic marker to honor the memory of the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga.

- Ota Benga found sanctuary in Lynchburg after being displayed at zoos in New York and St. Louis in the early 1900s.

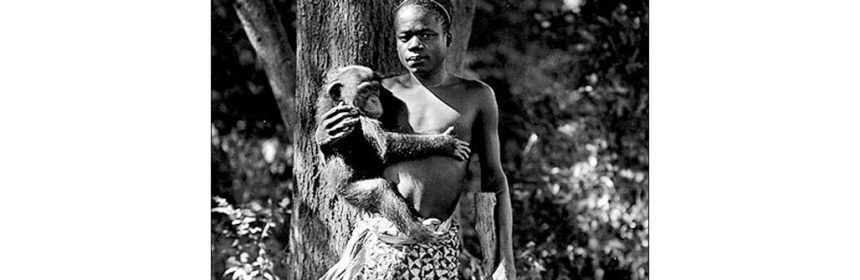

Among the hills of Lynchburg’s White Rock Cemetery lies the body of a Congolese pygmy named Ota Benga, who found deliverance in the Hill City after being displayed for his appearance at the Bronx Zoo’s Monkey House in the early 20th century. Where exactly Benga is buried remains unknown—decades of neglect caused the cemetery itself to be forgotten up until 1998 when it was rediscovered.

Despite the 101-year span between now and the day he killed himself on Seminary Hill, the memory of Benga has not been completely erased.

Formerly known as Mbye Otabenga, and later as Otto Bingo by Lynchburg residents, Benga and his incredible story have been depicted through movies and books. Brooklyn-based band Piñataland paid homage with a song titled “Ota Benga’s Name.” He even has a MySpace page.

And Benga was once again remembered Sept. 16 as the city of Lynchburg unveiled a historic highway marker in his memory.

The News & Advance reported more than 50 people gathered that Saturday morning to dedicate the marker at the intersection of Garfield Avenue and Hewitt Street. Among the crowd was Lynchburg Africa House Director Ann van de Graaf, Benga’s biographer Pamela Newkirk and others whose ancestors had welcomed the man into their city.

During the ceremony, Lynchburg Mayor Joan Foster announced Sept. 16 to be Ota Benga Remembrance Day.

“I want this to be remembered as a day of remembrance for Ota Benga,” Foster said at the ceremony. “His story touches me deeply.”

Benga had been living in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the turn of the century when his Mbuti tribe was virtually exterminated by the Force Publique—a group of Congolese and Belgian soldiers under the King of Belgium’s command.

The soldiers killed Benga’s wife and two children, and he was subsequently sold into slavery. In 1902, he was eventually traded for what van de Graaf said was salt and a piece of cloth to South Carolinian explorer Samuel Verner.

Verner had been commissioned by the St. Louis World’s Fair to venture out and retrieve Africans for an exhibition. He convinced Benga to travel with him, and two years later, he was a hit at the World’s Fair. People flocked to witness his 4-foot-10-inch, 104-pound frame. If they paid Benga five cents, he would flash his pointed teeth—”Gim’ nick, show teef,” he would allegedly say.

After the exposition, Verner brought Benga back to Africa, where he tried to readjust back to normal life while exploring the continent with Verner. But after his second wife died, Benga returned to America with his companion, and entered into an unorthodox living situation at the American Museum of Natural History in August 1906 and later, the Bronx Zoo.

There, he was free to roam the facilities, often helping employees take care of the animals and befriending an orangutan named Dohong. However, Zoo Director William T. Hornaday had different ideas, moving Benga’s hammock in a vacant cage of the zoo’s Monkey House and convincing him to shoot targets with a bow and arrows.

The New York Times caught wind of the Bronx’s newest resident, according to the Sept. 9 issue bearing “Bushman Shares a Cage With Bronx Park Apes” as its headline.

September 1906 saw 220,000 patrons of the zoo—double the number of visitors from September a year before. Upon entering the park, many would head straight to see Benga—billed as “The Missing Link”—wrestle with Dohong or play with his weapons.

Pamela Newkirk, author of “Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga,” writes of the damage the crowd inflicted upon the African.

“Benga became the object of pointing fingers, audible gasps, and bellowing laughter,” Newkirk wrote. “He did not initially comprehend their language, but could feel both the sting of their scorn and the pang of their pity…[He] could see his humanity…monstrously distorted.”

The exhibition, however, was short lived. Despite the grotesquely substantial enthrallment of the crowd, opposition quickly grew. New York’s African-American community was outraged, and Hornaday finally released Benga from his care.

The Mbuti pygmy spent the next decade of his life trying to adjust to American culture. In 1910, he relocated to Lynchburg, which became his sanctuary for the rest of his life.

Here, he enrolled in Virginia Theological Seminary, living with the school’s president, Hunter Hayes, for the next six years. He befriended African-American poet Ann Spencer, who taught him English, and worked at a nearby tobacco factory.

“He was so badly treated in New York at the zoo, and also in St. Louis,” van de Graaf told the News & Advance in a March interview. “But in Virginia, here in Lynchburg, he was happy… Here he found some peace, I think.”

But whatever peace he found was not enough. His desire to return to Africa grew stronger, as did his despair when the emergence of World War I hindered his plans to do so. On March 20, 1916, Benga shot himself in the heart, possibly out of torment at the hands of the 7,000 miles separating him from his home.

Over a century later, the marker now stands on the last street Benga walked, its inscription relaying his tragic story to anyone who might walk by. During the ceremony, Newkirk said the marker—the brainchild of van de Graaf— not only pays respect to Benga, but also to the city that sheltered him.

“Lynchburg gave this tragically displaced stranger home and semblance of family,” Newkirk told the crowd, as reported by the News & Advance. “This marker reflects your city’s values and highest ideals. So as you honor a man whose soaring humanity could neither be tarnished nor erased by the inhumanity of others, you illuminate your own.”

Thank you, Lynchburg and Liberty, for honoring this poor soul.

This apparent American and Belgium crime to humanity so widely effected Mr. Mbye Otabenga (Ota Benga) and his family that I suspect none of his family even remains to be informed. Although, in this instance much good has been achieved, we are left to do all that is possible to achieve even greater good in all forthcoming outcomes.

This tragic story is the outworking of social Darwinism, the practical outworking of Darwin’s theory of evolution. Thankfully the social application has fallen out of favor, but the biological theory is still taught in mainline schools from grade schools on up. Thankfully, there is now overwhelming evidence that Darwin had is completely wrong and there is zero evidence that unique species arise from random (chance) mutations (errors in genetic transmission) plus natural selection. Sadly, the lie remains in vogue except for those willing to truly examine the evidence.