Capturing champions since ‘73

Les Schofer, Liberty University’s senior photographer, highlights the school’s history while making his own

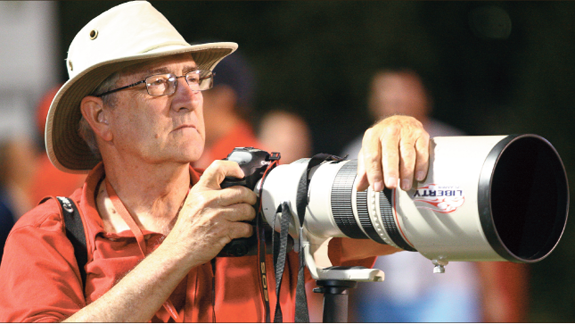

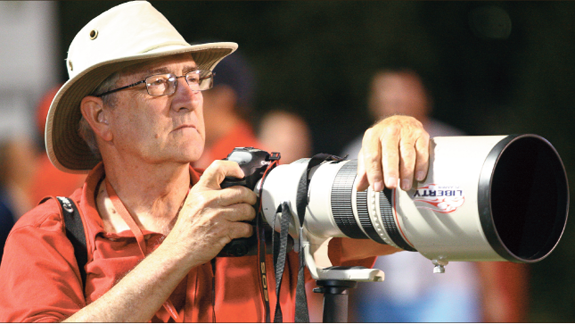

Picture hunting — Schofer, equipped with his familiar safari hat and photography gear, knows where to look to find the best shots on the field of play. Photo credit: Ruth Bibby

Flames fans call him “Safari Man.” He circles the field at Liberty University football games fully armed, ready to shoot — photographs. The loose-brimmed khaki hat earned him the nickname. A hat fit for the Sahara sun provides shade for him as he goes from one end of the field to the other in search of the perfect shot.

His shoulders carry the weight of more than 32 pounds of gear as he follows the action up and down the field. Poised at the end zone, he waits, he watches. Just as the Flames score their first touchdown, he fires. Like a skilled hunter, Les Schofer prepares to shoot the action at the precise moment.

For nearly 40 years, Schofer has captured the growth and history of Liberty University with his camera. His prize shots are on display across campus, greeting visitors coming to the world’s largest Christian university. As the senior photographer for Liberty, Schofer delivers pictures that are not just photographs of events or buildings, but demand a second glance as they tell a story through the action, emotion or colors he draws from his subject.

As a member of the professional group, University Photographers Association of America (UPAA), Schofer has been recognized as the photographer serving his institution for the longest period of time in the country. In so doing, he also became the only UPAA photographer to have recorded the start of his school and to still be shooting it today.

Designed in 1980, this pin expressed the essence of Jerry Falwell Ministries. Connie Schofer, Les’ wife, first suggested that he place it in a red rose.

“What Les contributes most is photographic expertise, but also, he just injects his personality into all that he does, whether it’s interacting with you or his images,” Joel Coleman said. “You can pretty easily tell a Les Schofer image, just because of who he is and how he translates who he is into the camera.”

As one of the full-time photographers for the university, Coleman has built his photography skill under Schofer’s guidance.

“When I say that Les (Schofer) has taught me most of what I know, that’s an understatement,” Coleman said.

What started out as an interest in high school has developed into a career in photography for Coleman. While working with Schofer, he moved from only volunteering to a full-time position in just two years.

“One summer, my job was to scan some of his images, you know, shot 30 years ago, that nobody had seen since. (It) was really eye opening to be able to see history that was made in the early days of the university and Dr. Jerry Falwell’s ministry,” Coleman said.

For every change on Liberty’s campus, Schofer was there. When bulldozers rumbled through the fields to reshape the hillside, or when students assembled with Falwell to pray in the snow for God to send money for the new campus, Schofer was there. Forty years have changed the appearance of the school, but not the passion of its senior photographer. Today, he is still capturing the growth and changes of the university in images.

Schofer entered the university not as a staff photographer, but as a new student in the second year of the Lynchburg Baptist College in 1973.

The beginning years of the yearbook were rocky, but Schofer managed to bring his knowledge from across the country. His time at Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara, Calif. let Schofer raise the yearbook to a higher caliber. Schofer spent time improving the yearbook, and then moved to a full-time position with Jerry Falwell Sr.’s ministry in 1975.

“One thing that characterized Dr. Falwell throughout his ministry was that he embraced every new piece of technology that came along, and I think that inspired me to do likewise,” Schofer said.

Through Schofer, Liberty adopted the use of digital photography when it was still a relatively new technology. He made a personal investment in his photography business by using digital cameras, something no one else was using in the mid-1990s. Because of his insight, Liberty was the first university to use digital images in its publications.

Scott Hill also held the position of photo editor of Liberty’s yearbook, Selah, before it went online. Hill went from the yearbook to working under Schofer, an experience he cannot put a price on.

“He knows more than anybody wants to know,” Hill said.

Home football games for Liberty meant Hill would follow Schofer, listening to the photography guru explain how to compose the best shot.

“If you listen and actually pay attention, you can learn a lot from him. I mean, we would spend a couple hours a day talking about photography,” Hill said.

But photography is not a technical, dry profession for Schofer. It is an avenue where professionalism sometimes takes a backseat to having fun.

On the sideline — I had been at Liberty for a year and a half when I shot this at City Stadium in 1974. I can guarantee that Jerry Sr. was thinking of the day we would have first-class facilities on our campus.

“He’s a fighter — strong guy — he lives like he’s a college student. Every photographer (who knows him) knows that,” Hill said.

Schofer knows how to roll with the punches his job throws his way. From equipment failure to unexpected glitches, Schofer stays calm. Errors remain hidden secrets to the subjects as he keeps his focus on producing the best shots.

“What makes the difference between a good photographer and a great photographer is the ability to come away with the images that you need, in less than ideal circumstances,” Coleman said. “(He is) very easy to get along with. In all of the photo adventures I’ve been on with Les (Schofer), (he’s) always able to solve problems.”

Schofer knows that more than a ball and player make a great sports shot. He soaks in the details of the event. From the background, to the point of view, to predicting the next play, Schofer takes in every detail that makes his shot.

“To me, I can’t feel successful if I just get an image of this particular play. I want it to look distinct,” Schofer said.

When yelling fans fill the Vines Center as they cheer on their Flames during the last seconds of a basketball game, he remains composed. A characteristic that Schofer said he and the late Falwell shared.

“(Falwell) had a very relaxed, colloquial, and sometimes surprising way of dealing with (stress). I think some of that rubbed off on me,” Schofer said.

Falwell was not just a boss for Schofer, but a friend who shared the same humor and baseball devotion.

“We could sit down and talk about anything, I guess, but it usually was about the New York Yankees. That was our point of contact. Anytime we got together, it usually was to talk about the joy or the sorrow of whatever the Yankees were doing at the time,” Schofer said.

When Falwell became involved with the Right to Life issue and developed the Liberty Godparent Home through Thomas Road Baptist Church, Schofer was all in. In 1982, it was another dream of Falwell, but today, the home sits on the outskirts of Liberty’s campus, offering a place for young mothers to decide whether to parent or put their child up for adoption.

The Godparent Home benefited not only from Schofer’s promotional pictures, but he and his wife, Connie, benefited from the Godparent home. They were the eighth family to place their name on an adoption waiting list.

“Within a year and a half, we had a little tiny baby girl, Stacy, who is now 28 years old,” Schofer said.

“She was an incredible student, and I think that’s proof there’s no genetic link between us,” Schofer said.

His wit hides in laugh lines on his face as his brown eyes watch, waiting to see if his audience catches his subtle humor.

Away from high-energy environments, Schofer sits back, enjoying every minute of life. A typical day in the Marketing Department involves Schofer poking fun at other photographers, followed by the half smile that they all know.

“If it was just a job for him, he wouldn’t necessarily care as much as he does,” Coleman said.

The construction of the new football stadium in 2010 gave Schofer a bird’s eye view of the campus as he climbed the bare cement towers above the construction to show each step of the stadium’s completion.

A freight elevator took Dr. Elmer Towns and Schofer to the roof of Green Hall when they climbed on top to shoot for the cover of “Walking with Giants.” His daredevil spirit sometimes ignores the wisdom of his gray hairs. Trips to Freedom Aviation airport also gave Schofer the chance to take aerial shots from the helicopter with the doors removed.

After shooting for almost 40 years, Schofer still has not slowed down. Cancer, a stroke, arthritis and retinal degeneration have not stopped him from doing what he loves.

“After you’ve been through something so serious, you say to yourself, ‘What else?’” Schofer said, “and I’m still doing anything I would be doing eight or nine years ago. I’m very thankful to God for that.”

I worked with Les on some of the early yearbooks. I will always appreciate the time he took to mentor encourage me. The time spent with Les was never wasted.